From a map, the Isle of Sri Lanka is like a small

piece of leaf-like gem cuddled beneath the Indian subcontinent.

Separated from the mainland by the shallow waters of the Palk Strait, it

is home of innumerable temples and massive architectural monuments; a

land matted by verdant scenery and lush foliage; and a place where the

first rays of sunlight never fail to augur the daily dissipation of the

evening mist. Sprawled across the Indian Ocean like jetsam buoyed up by

the sea, the contours and geography have both been likened to a new

picked pear and to a piece of tobacco leaf.

Yet, for all its beauty and magnificence, Sri Lanka

is a place bath in tears. Because for the past several years since its

independence, the country has been the scene of ethnic turmoil and civil

strife, of dreadful days and sleepless nights. For decades, its lush

earth has grown accustomed to the sound of gunfire and the stench of

rotting flesh, to the burst of mortar and the staccato of armalite.

Hidden behind its forests' enclaves, a dozen or so armed groups lie in

wait, ready to strike at the slightest provocation and ready to leave

behind trails of blood and gore.

thus, despite its diminutive size, the country has

gained international disrepute for having the largest number of reported

"disappearances" and accompanied by an unending cycle of violence.

A Tragedy Waiting to Unfold

Ironically, its present political situation

demonstrates Sri Lanka's long tradition of formal democratic rule. Since

its independence in1948, elections have been dominated by two rival

political parties: the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lankan

Freedom Party (SLFP).

While violence has always been a permanent fixture in

Sri Lankan politics, things blew out of proportion in 1971 when the

Marxist-inspired Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP / People's

Liberation Front) launched an armed insurrection against the government

of Prime Minister Sirimawo Bandaranaike which came to power the previous

year. Despite support from young segments of the Sinhala ethnic group in

the south, the rebellion was later crushed by governemt forces. In the

resulting crackdown, 18,000 people were reported to have been killed and

disappeared, presumably on government orders. Others, including

thousands of sympathizers, were arrested and given harsh prison terms.

This ensuing reaction marked the beginning of the "culture of

disappearance" from which the country has not fully recovered.

For six years, the JVP remained underground until

1977, when UNP won the elections. under its new Prime Minister Junius

Richard Jayewardene, the government ordered the release of the remaining

JVP prisoners including its leader Rohana Wijeweera. As a result, the

JVP then began to get involved in open politics, fielding candidates in

elections on the basis of Sinhala nationalism. It found adherents not

only among the youth and university students but also among Buddhist

monks and even a few military officers fighting against separatist

insurgents in the north. It even joined the 1982 presidential elections,

with Rohana Wijeweera gaining four percent (4%) of the total votes cast.

Events, however, turned for the worse when a new

round of communal violence broke out in 1983, between the majority

Sinhala and the minority Tamils in the northeast. Known as "Black July",

the event was triggered by the killing of 13 Sinhala army personnel in

the north by Tamil militants resulting in retaliatory moves by the

Sinhalese.

To prevent further destabilization, the government

declared a State of Emergency and banned several groups critical of the

government, including three leftist parties - the Communist Party, the

Nava Sama Samaja Pakshaya (NSSP / New Socialist Party) and the

JVP. During this period, the Emergency Regulations (ERs) came into

force, granting security personnel wide authority to arrest and detain

perceived enemies of the State without being charged or tried for long

period of time.

Forced once again to go under ground, the JVP began

preparations for another armed rebellion against the government. In

1988, it called on the electorate to boycott the provincial council

elections scheduled for the 19th of December of the same year and

organized anti-government demonstrations in the south.

There was a temporary respite when the elected

president, Ranasinghe Premadasa of the UNP, lifted the State of

Emergency in January 1989. The JVP, however, continued its armed

resistance, calling on strikes and mounting assassination campaigns

against government officials. Faced by the growing intransigence of the

JVP, Premadasa re-imposed Emergency Regulations on June 20, 1989 and has

not been rescinded ever since.

By the following August, a massive anit-JVP campaign

was launched to finally crush the looming insurgency. Dubbed as

"Operation Combine", the campaign involved the entire military and

police establishments and was placed under the command of the Army Chief

of Staff. In November 1989, the government announced the arrest and

subsequent death of Rohana Wijeweera and several other JVP leaders after

military operations in Ulapana. Suspicions of liquidation and "foul

play" however soon emerged after is was discovered that the bodies were

immediately cremated "under conditions of maximum security" before any

inquest or post-mortem examinations could be held. Rumors have it that

the JVP chief was not killed in armed skirmish with security personnel

but was shot in Colombo where he was taken while still in government

custody.

Following Wijeweera's death, the remianing JVP

Politburo members fell in government hands by January of 1990.

Mopping-up operations however continued throughout the entire year,

allowing both military and paramilitary forces to arrest, detain and

execute real and imagined members of the JVP.

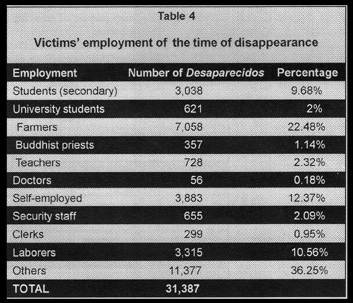

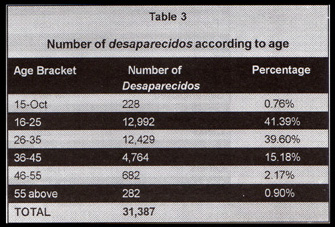

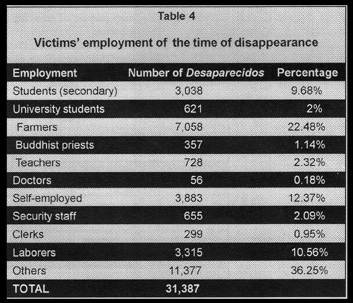

As a result of the reprisal, about 60,000 have

mysteriously disappeared within the two year period of 1989-1990,

according to Amnesty International. Unofficial reports however indicate

that close to 100,000 had been abducted and disappeared, most of whom

being secondary or university students suspected of having links with

JVP. Buddhist monks were also victimized and in some instances, in lieu

of the suspects' relatives, were arrested.

Tigers on the Prowl

But before the the government could even neutralize

the JVP, trouble was already brewing in the northeast. Fuelled by

Sinhala discrimination and ethnic resentment, skirmishes occurred

between minority Tamils and security personnel starting in the

mid-1950s. The attacks became more frequent by 1977 until it became a

full-scale war after the communal riots of 1983.

The root of the problem dates back to the time of

independence when in 1948, the new republic inherited the Soulbury

Constitution from the British. The Charter's provision for a highly

centralized and unitary state was later reaffirmed in the Republic

Constitution of 1972 and in the amendments of 1978 which introduced a

president as chief executive. Further animosity was created when then

Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike made Sinhalese the national

language.

By this time, agitated Tamil intellectuals began

demanding for greater autonomy and wider political authority, leading to

the formation of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). In its First

National Conference in 1976, the TULF demanded the creation of a

separate Tamil State called "Tamil Eelam", identifying the Northern and

Eastern Provinces as their traditional "homeland". Hoping to attain

their goals through legal and non-violent means, their expectations were

soon dashed when the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) began

attacking police installations in 1978.

To prevent the spread of the separatist rebellion,

the central government enacted the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) in

1979, effectively eliminating judicial checks on law enforcement.

Intended to be enforced upon the troubled areas for a period of one

year, the PTA became a permanent law through an amendment introduced in

1982. The authorities also expanded their scope throughout the entire

island, resulting in more human rights violations.

But instead of emasculating the armed uprising,

government repression merely galvanized Tamil resistance even more. in

the following years, other Tamil separatist groups were formed,

determined to wrest independence from Sri Lanka by force.

Uncanny Twist

Bled dry by protracted guerilla campaign, the

government of Sri Lanka sought the assistance of India then under the

leadership of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. In July 198, the

Indo-Sri Lanka Accord took effect, allowing the entry of Indian troops

to take charge of security in the northeast. Labeled as the Indian

Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF), they were specifically created to disarm the

militants and end the military stalemate.

Bled dry by protracted guerilla campaign, the

government of Sri Lanka sought the assistance of India then under the

leadership of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. In July 198, the

Indo-Sri Lanka Accord took effect, allowing the entry of Indian troops

to take charge of security in the northeast. Labeled as the Indian

Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF), they were specifically created to disarm the

militants and end the military stalemate.

Aside from this measure, other conciliatory gestures

were also made. As provided in the Accord, elections were scheduled for

1988 to elect officers to an island-wide Provincial Council system with

considerable administrative powers as well as extending general amnesty

to all political prisoners arrested under the PTA and similar emergency

laws.

Enticing as it may seem, the Accord suffered from one

fundamental defect: Tamils, who were the ones primarily affected by the

war, were not party to the agreement. Hence, LTTE violence continued,

and the rebels called for a boycott of the provincial council elections.

In the aftermath of the elections, the militant Eelam

People's Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) gained control of

most of the provincial councils in the northeast. Allying itself with

the IPKF, the EPRLF began to launch counteroffensive operations against

the rival LTTE.

Renewed Violence

Unable to break the back of the insurgency and burdened by the internal

affairs of another country, India withdrew its troops form the island in

March 1990, but not before it could prevent another series of clashes

between the LTTE and the Tamil National Army (TNA), a new armed

formation created through the combined elements of the EPRLF and other

pro-India forces. In June of the same year, the central government in

Colombo began mobilizing its forces, sending regular troops to the

troubled regions in the north. By mid-1990 however, Jaffna fell under

LTTE control and would remain in its hand until late 1995, after

yielding to massive counter-assaults by the Army.

The Tigers, however, remained unfazed. Placed on the

defensive, they launched a series of assassinations and bombing attempts

in the urban centers, targeting politicians and security officials,

usually carried out by crack suicide squads. In 1993, the LTTE

assassinated President Premadasa. They also killed Indian Minister Rajiv

Gandhi for his role in the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord. In 1999, a suicide

bomber blew a political rally by the People's Alliance injuring re-electionist

President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga.

Last year, the Tigers made another attempt to regain

their former stronghold, forcing the government to withdraw its troops

situated in the Elephant Pass. In retaliation, the government suspended

the region's development aid for three months and banned the acquisition

of imported arms.

In the ensuing conflict, over 1,500 Tamil civilians

have already "disappeared". In 1995 alone, 55 cases were reported. In

1996, about 500 people have mysteriously "disappeared", and the

following year, 100 cases were documented, mostly coming from Jaffna,

Batticaloa, Mannar and Kilinochchi.

Enter the People's Alliance

In August 1994, the People's Alliance (PA), a

coalition of parties under the SRFP, won the parliamentary elections

that ended the UNP's 17-year grip on power. Winning 105 of the total 225

seats, the PA forged an alliance with the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress and

other opposition parties enabling them to muster a majority of 113 seats

as opposed to the UNP's 94. In the presidential elections the following

November, PA leader Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was elected as

the country's new Chief Executive.

In August 1994, the People's Alliance (PA), a

coalition of parties under the SRFP, won the parliamentary elections

that ended the UNP's 17-year grip on power. Winning 105 of the total 225

seats, the PA forged an alliance with the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress and

other opposition parties enabling them to muster a majority of 113 seats

as opposed to the UNP's 94. In the presidential elections the following

November, PA leader Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was elected as

the country's new Chief Executive.

After being sworn into office, the President

manifested her intention to seek a peaceful solution to the ethnic

problem and improve the country's human rights situation. She ordered

all incidents of human rights violations investigated and that the

perpetrators be brought to justice. In 1997, the government ratified the

Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights and established a permanent agency called the Human Rights

Commission (HRC) to investigate cases of human rights violations. She

also thrice invited the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or

Involuntary Disappearance (UNWGEID) to visit Sri Lanka, the latest of

which was in 1999. This visits were able to gather evidence and

established the extent of the disappearances. These, however, failed to

yield any concrete actions for the victims and their families.

In November of 1996, in response to the on-going

hostilities in the north, a Board of Investigation under the Ministry of

Defense was set up to investigate disappearances that were allegedly

committed in Jaffna. Until today, however, the public still awaits the

report of the investigation.

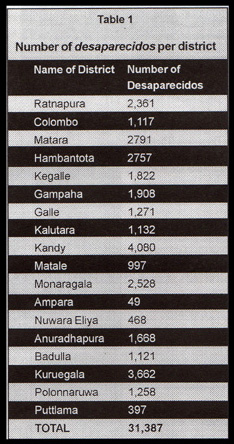

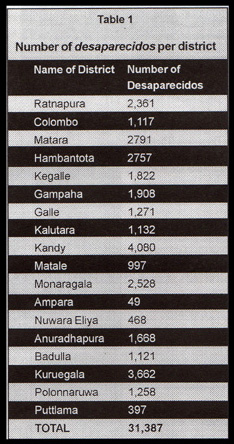

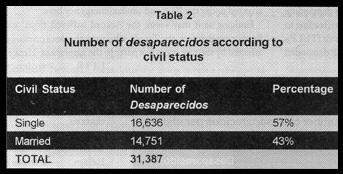

Probing the Abductions

On 27 December 1994, the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on

Disappearances (PCID) was formed to probe into the phenomenon of

involuntary disappearance in the country. This soon turned out to be the

first of three Presidential Commissions created for that purpose,

followed by the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into the Involuntary

Removal of Persons (PCIIRP) and the Presidential Commission on

Involuntary Disappearances. In a period of two years since they began

work in 1995, the Commissions were able to look into 27,000 cases of

disappearances, most of which were perpetrated by the State agents of

para-military groups in the course of the anti-insurgency campaigns.

Through their inquiry, the Commissions were also able

to discover the various means in keeping these incidents unrecorded -

from the use of unmarked vehicles by the abductors to the refusal of the

police to document the complaints. There were also instances

wherein local authorities would disallow the families from either

identifying or taking possession of the bodies and outrightly refuse the

issuance of death certificates. Their reports also disclosed that in

most operations, police preferred "abductions" over "arrest", thus

implying its intent to physically eliminate the suspects.

In the course of their investigations, the

Commissions discovered 12 mass graves located in different parts of the

island. They are:

1. Hokandara mass grave

2. Essela School mass grave

3. Wavulkelle mass grave

4. Walpita Government Farm mass grave

5. Ambaghahenakanda mass grave

6. Bermulla mass grave

7. Kottawakella, Yakkalamulla mass grave (Galle District)

8.Dickwella mass grave at Heendeliya

9. Diyadawakella, Deninaya mass grave

10. Wilpita Akuressa mass grave

11. Angkumbura mass grave

12. Suriyakanda mass grave (Monaragala District)

They were also able to establish the identity of more

than 3,000 perpetrators. Red tape and bureaucratic tediousness however

have derailed the process, with only 400 cases heard in court.

Sins of Omission

Unfortunately, the investigations were not without

controversy. As early as 1994, the PCID was severely criticized after it

was announced that the Commission was only mandated to investigate cases

that occurred after January 1, 1998 despite the fact that most

disappearances happened even before the PTA was promulgated in 1971.

Bowing to public pressure and the threat of foreign partners to withdraw

vital development aid, the Sri Lankan government formed the PCIIRP. The

new Commission, unfortunately, proved to be another toothless tiger

since it was authorized to probe disappearances that occurred after

January, 1991.

The government was also criticized for its seemingly

obnoxious compensation package. Under the previous UNP regime,

government employees received greater reparation than those outside of

the bureaucracy, with the former receiving between Rs. 75,000 to Rs.

150,000 as compared to the latter who only receive a measly sum of

around Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 50,000. Apparently, the package was made at the

neight of the government campaign against the JVP and the LTTE, with the

primary purpose of providing compensation to 6,000 UNP supporters.

To correct this imbalance, the Presidential Commission on Involuntary

Disappearances recommended that a uniform amount of Rs. 150,000 be paid

equally to spouse and children of the disappeared, with the widow

receiving Rs. 75,000 and the remaining balance to be shared by the

children. But the government decided to instead give the families a

monthly life allowance of Rs. 500. Though it has complemented its

compensation package by giving minor food allowance under the

Samurdih (Prosperity) Programme, government assistance remains

inadequate. More so, only 13,000 have been compensated so far.

But apart from government incompetence, the work has

also been hampered by the victims, own limitations. Living ,mostly in

rural communities amidst severe economic hardships, most victims find

little time for protest campaign and courtroom proceedings. Most of them

are also threatened and harassed by the culprits, thus dissuading some

of them from pursuing their cases. The UNP and the security forces have

also utilized their influence to create all sorts of legal impediments

and abort justice. Few lawyers are also interested in human rights

issues, preventing the victims and concerned NGOs from soliciting free

services.

What Now?

Seen from all angles, Sri Lanka's dubious human

rights record has surely become a moral dilemma. With 60,000 reported

cases, it has become the country with the largest volume of

disappearances - a title which is certainly no source of pride or honor.

The irony of it is that it occurred in a nation that takes pride in

having a recorded history spanning several millennia; and for a people

to achieve such a level of accomplishment, brutality is the very last

thing that could be expected from them.

To keep the Sri Lankan people from forgetting its

dreadful past, the Organization of Parents and Family Members of the

Disappeared (OPFMD) has declared April 4 as the National Day of

Disappeared Persons. Though this date has yet to be officially

recognized by the Sri Lankan government, the Organization intends to use

this yearly commemoration as a springboard to the on-going justice

campaign and a means to prevent such atrocities from recurring.

But fate would have it otherwise, and unless the

Tamil and the Singalese begin to settle their differences and exorcise

the monster that have ravaged their land, Sri Lanka will always be a

place of broken serendipity.

Bled dry by protracted guerilla campaign, the

government of Sri Lanka sought the assistance of India then under the

leadership of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. In July 198, the

Indo-Sri Lanka Accord took effect, allowing the entry of Indian troops

to take charge of security in the northeast. Labeled as the Indian

Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF), they were specifically created to disarm the

militants and end the military stalemate.

Bled dry by protracted guerilla campaign, the

government of Sri Lanka sought the assistance of India then under the

leadership of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. In July 198, the

Indo-Sri Lanka Accord took effect, allowing the entry of Indian troops

to take charge of security in the northeast. Labeled as the Indian

Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF), they were specifically created to disarm the

militants and end the military stalemate.

In August 1994, the People's Alliance (PA), a

coalition of parties under the SRFP, won the parliamentary elections

that ended the UNP's 17-year grip on power. Winning 105 of the total 225

seats, the PA forged an alliance with the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress and

other opposition parties enabling them to muster a majority of 113 seats

as opposed to the UNP's 94. In the presidential elections the following

November, PA leader Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was elected as

the country's new Chief Executive.

In August 1994, the People's Alliance (PA), a

coalition of parties under the SRFP, won the parliamentary elections

that ended the UNP's 17-year grip on power. Winning 105 of the total 225

seats, the PA forged an alliance with the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress and

other opposition parties enabling them to muster a majority of 113 seats

as opposed to the UNP's 94. In the presidential elections the following

November, PA leader Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was elected as

the country's new Chief Executive.