Katipunan Road in the town of Labangon, Cebu province

is a usually busy street, with endless rows of vehicles treading along its

slender, cemented path like like passing salmons in a narrow stream.

Situated five kilometers away from the provincial capital, Katipunan could

well be described as the epitome of life in the southern suburbs - busy,

noisy and feisty, albeit unbereft of that genial rustic element that is so

common in this part of the Philippines. Yet on the 11th of July 1985, this

same stretch of land known for its clatter and humdrum suddenly fell

silent, exuding a sense of the funereal as it huddled itself in its own

eerie quietude.

For at 9 o'clock in the morning, a white Ford Cortina

with a hard black top appeared along Katipunan, with two motorcycles

trailing closely behind. As the small caravan halted in a nearby

Sing-Along, armed men in civilian clothes alighted from the vehicles,

donning assault rifles and hand-held radios. Around 3:45 in the afternoon,

a man on blue motorcycle was noticed approaching Cabarrubias Street from

Katipunan Road At that precise moment, the white Cortina swung around,

blocking its path. As the two other motorcycle came from behind to

complete the entrapment, armed hooligans surrounded the victim and cocked

their M-16s, pointing their deadly nozzles at the surprised motorcyclist.

Before shoving him inside the car, one of the assailants seized the man's

bag and removed his crash helmet, revealing the muffled face of Fr. Rudy

Romano - Redemptorist priest and anti-Marcos oppositionist. Shouting "Ang

akong motor" (My motorcycle), Fr. Rudy beamed a confident smile, as he

saw a number of bystanders witnessing his arrest. As it later turned out,

that was to be the last strand of hope that was to be gleaned from him by

the public eye.

Fifteen years and four administration later, Fr. Rudy

remains officially missing; and neither his fate nor his whereabouts has

been divulged by the military, by his abductors or by the intelligence

community. Even up to this time, his disappearance has generated endless

questions and speculations, turning a once-frantic search for a missing

person into a motivating force for national introspection. As a member of

the Catholic clergy and respected leader of the Task Force Detainees of

the Philippines (TFDP), Father Rudy has since become a poignant symbol for

all desaparecidos and a rallying icon for both defenders and

advocates of civil liberties and human rights.

Used initially as a political tactic to silence the

opposition against the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos, involuntary

disappearance has since become the underlying legacy of the latter's

corrupt administration. Starting with the abduction of militant student

leader Charlie del Rosario in 1971, the number of disappeared has now

exceeded the thousand-mark, and is expected to increase gradually for an

indefinite period of time.

While disappearances may have been perpetrated under an

erstwhile democratic regime, the declaration of Martial Law in 1972

clearly gave the military and other security agencies the legal cover in

their punitive operations. Armed with near carte blanche authority,

State agents arrested suspected dissidents at will, resulting in gross

human rights violations including 759 reported cases of involuntary

disappearance under the incumbency of then-President Marcos.

The Usual Suspects

Viewed from any angle, it is clear that the abductions

were government reactions to the growing insurgency in both the urban

centers and countryside. Faced with multiple armed challenges from the

communist New People's Army (NPA) to the separatist Moro National

Liberation Front (MNLF) and its various splinter groups, the government

used disappearances to cajole the population and weed out potential rebels

and sympathizers. In most instances, the escalation of armed conflicts is

accompanied by intensified perpetration of abductions and disappearances,

turning a savage guerilla war into a government campaign against its own

people.

Consequently, a large portion of those who disappeared

were or had been members of legally constituted sectoral and human rights

organizations which the military claims to have direct links with the

leftist underground or are sympathetic with communist cause. Among the

targeted groups are peasant /farmer organizations like Kilusang

Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMU) / Peasant Movement of the Philippines)

and labor unions such as the Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) May One Movement).

Other victims include ordinary citizens from all sectors of society who

have been very critical of government policy and have voiced their

criticisms in non-violent manner.

In recent years, the military has utilized more

sophisticated means of emasculating the opposition - employing vigilante

groups, militia units and paramilitary forces in their counter-insurgency

operations. They have also devised paralegal means to corrode and weaken

the insurgency's mass base by targeting open or legal non-governmental

organizations suspected of being front groups for the CPP-NPA. Once

identified, members of the said NGOs are subsequently subjected to

stigmatization and "red-labeling", thus turning them into legitimate

targets by counter-operatives. Most often than not, they become the

object of constant harassment and intimidation, while others become

targets of physical abuse. In a majority of these cases, such practices

are carried out by poorly trained and ill-disciplined members of the

paramilitary. Though in total violation of their rules of engagement,

abductions and other abuses have been committed with blind toleration (if

not outright sanction) from military commanders, making human rights

violations an intrinsic element in

government's anti-insurgency operation.

Based on existing records, the institutions that have

been commonly implicated in such systematic wrong-doing are the Armed

Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the Philippine National Police (PNP), the

now-defunct Philippine Constabulary (PC) and members of various militia

organizations such as the Citizens' Armed Forces Geographical Unit (CAFGUs)

and the Marcos-era Citizens Home Defense Forces (CHDF).

The pattern of involvement was even verified by the

United nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance (UNWGEID)

through a report that was released in 1991. In the said document, the

Group asserted that, "...most cases of disappearances are to be ascribed

to members of the military, the police and vigilante groups...the

government CAFGUs and, to a lesser extent, civilian volunteer groups

should be added." This was further corroborated in a separate study

conducted by Amnesty International, which concluded that in most cases,

victims who subsequently "reappeared" were held in custody by either

military or police authorities from a period of one week to two months.

Poetic In-justice

Ironically, despite the past and present commission of

enforced disappearances, the Philippines itself has been a party to a

number of international treaties and agreements designed to promote and

protect basic human rights. The most prominent is the United Nations

Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General

Assemble on on December 10, 1948 and to which the Philippines in one of

the first signatories.

The country was also a signatory to the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which states, among other things,

that "all persons shall not be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman

or degrading treatment or punishment" (Article 7). It also stipulates that

"no one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in

accordance with such procedure as are established by law" (Article 9). The

Covenant further guarantees that "anyone who has been the victim of

unlawful arrest or detention shall have an enforceable right to

compensation" and that "everyone shall have the right to recognition

everywhere as a person before the law" (Article 16).

It did not even oppose the adoption of the UN

Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances when it was presented to the UN General Assembly on

December 18, 1992. Because of its stance, the government is thus bound to

"take effective legislative, administrative, judicial and other measures

to prevent and terminate enforced or involuntary disappearance in any

territory under its jurisdiction" as stipulated in Article III. Article

XIV also mandates that those suspected of perpetrating an enforced

disappearance shall "be brought before competent civil authorities of the

State for the purpose of prosecution and trial" and that "all States

should take any lawful and appropriate action available to them to bring

all persons presumed responsible for an act of enforced disappearance

found to be within their jurisdiction or within their control, to

justice."

In December of last year, the country also ratified the

Rome Statute Establishing the International Criminal Court - a judicial

body under the auspices of the United Nations which has the power to hear

and decide cases involving genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity,

aggression and enforced or involuntary disappearances which have been

committed within the territory of the State parties.

Given these precedents, the Philippine government

therefore has rescinded on its international obligations, signing

documents left and right only to pay lip service later on.

One Step-Forward, Two Steps Backward

Though the Marcos regime has become synonymous with

human rights violations, the incidence of disappearances has not been

mitigated even after his ouster from power and the subsequent restoration

of democratic rule. Under his immediate successors Corazon Aquino for

example, the number reported cases of involuntary disappearances has

reached 830, far exceeding the levels during the Martial Law period. And

while involuntary disappearances have markedly declined in recent years,

with 66 cases recorded during Ramos's incumbency and with at least 27

instances committed under the Estrada administration, the total number of

1,682 is still relatively high within the context of the Asian region.

Moreover, of these figures, only 35 have so far been exhumed while a very

small number have resurfaced alive. The fate of the rest, however, remains

uncertain.

To remedy the situation, then President Corazon Aquino

formed the Presidential Commission on Human Rights (PCHR) shortly after

her assumption to power in 1986 to investigate various cases of violations

involving political rights. Headed by well-respected Senator and street

parliamentarian the late Jose "Pepe" Diokno, the PCHR was transformed into

an independent quasi-judicial constitutional body in 1987. Dubbed as the

Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and with 13 regional offices through out

the country, its expanded mandate includes civil, economic and

socio-cultural rights.

Despite its noble intentions however, the Commission

has been hampered by severe institutional limitations. While it may

investigate cases of human rights violations and recommend the same to the

Department of Justice (DOJ) or to the Office of the Ombudsman, the CHR

lacks any prosecutory power of its own. Because of this impediment, most

witnesses are wary of identifying themselves, since they are not given the

proper protection that can only be accorded by a proper court of law.

This however, does not mean that reforms and

improvements are in the offing. Under the Ramos administration, a

Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) was singed between the Justice Department

and the Commission on Human Rights allowing the latter to serve as a

collaborating counsel along with DOJ lawyers in the prosecution of human

rights -related cases. Several moves in Congress have also been made which

seek to grant prosecutory powers to CHR. To further beef up these efforts,

former President Ramos also formed, through an executive order the "Task

Force Disappearance". Spearheaded by the CHR, the Task Force includes the

DOJ, the PNP, the AFP and various human rights NGOs. The undertaking,

however, proved nothing. this, according to most NGOs, was due to the fact

that the AFP and PNP were part of the initiative, which were the most

notorious institutions suspected of committing human rights violations.

Yet, despite its lack of success, parallel efforts were

also made at the legislative department, with Senator Sergio Osmeņa III

and Representative Bonifacio Gillego filing a resolution calling on the

Philippine government to ratify the UN Declaration on the Protection of

All Persons from Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. Another

resolution was also submitted supporting Amnesty International's 14 Point

Program for the Prevention of "Disappearances". These measures however,

were merely passed by the committee and were not approved by the plenary.

More so, Congress through the initiative of AFAD

Chairperson Edcel C. Lagman, in 1993 had allocated P4 million ($153,000)

for the welfare and rehabilitation of families affected by involuntary

disappearances as well as the surviving victims. This was then increased

to P5 million ($193,000) in subsequent annual budgets. This allocation

however is subject to a very stringent colatilla, with the burden of proof

placed squarely on the shoulders of the victims' families, most of whom

are deprived of the most basic access to the prescribed legal requirements

that would prove both the disappearance and their level of kinship with

the disappeared.

Civil society groups have also made significant

contributions in the over-all effort. The Families of Victims of

Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) for example, has been active in

data-gathering and in its numerous support programs. it also involved in

organizing forensic search missions in order to locate, identify and

recover the remains of the dead desaparecidos. Unfortunately, its

work has also been met by severe difficulties. Most often, witnesses are

fearful of coming out in the open lest they suffer from possible reprisal

from those responsible for the atrocities. There were also cases wherein

the victim's remains were removed from the burial site shortly before

exhumation.

Civil society groups have also made significant

contributions in the over-all effort. The Families of Victims of

Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) for example, has been active in

data-gathering and in its numerous support programs. it also involved in

organizing forensic search missions in order to locate, identify and

recover the remains of the dead desaparecidos. Unfortunately, its

work has also been met by severe difficulties. Most often, witnesses are

fearful of coming out in the open lest they suffer from possible reprisal

from those responsible for the atrocities. There were also cases wherein

the victim's remains were removed from the burial site shortly before

exhumation.

But what would probably the most difficult problem of

FIND and all other human rights groups is that until now, most

perpetrators remain unpunished. The extent of impunity in the Philippines

has been so great that it was even noted by the UNWGEID. From 1987 to 1990

for example, the CHR received 7,944 complaints of human rights violations.

of this number 1,509 cases were filed in court and only 11 cases yielded

punishment against the offenders. Furthermore in the 1998 Report of the

UNWGEID, the Philippine government sought the deletion of 49 cases in the

former's list of desaparecidos and another 350 cases to be reviewed

by the military - the very institution that was primarily involved in most

(if not all) of these abductions.

To make matters worse, only a small number of families

have so far benefited from financial assistance program given by

government (which approximately P10,000 or $200 per family). As of this

writing, approximately 300 families were given financial assistance and

more are still awaiting justice.

Uncanny Twist

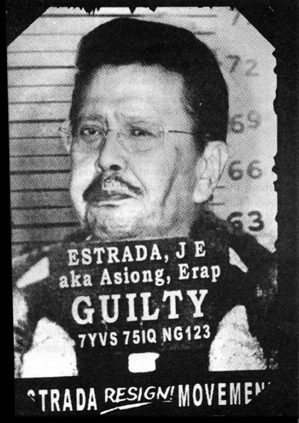

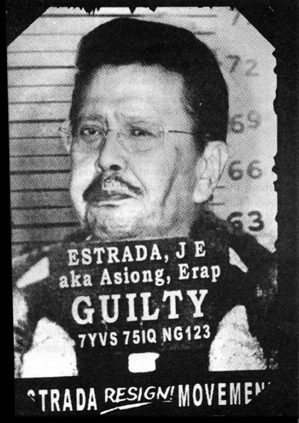

The phenomenon of involuntary disappearance however,

had a very uncanny twist with the election of Joseph Ejercito Estrada to

the presidency in 1998. A former movie actor turned politician, Erap

(as he is called by most Filipinos) was able to successfully mix

presidential reverence with pop icon fanaticism - a trait that is so

common among the stars and bigwigs of the silverscreen. Turning his

legions of adorning fans into a solid electoral base, Estrada was able to

defeat other seasoned politicians though sheer imagery and a populist dose

of pro-poor rhetoric, charging his campaign with the slogan "Erap Para

sa Mahirap (Erap for the Poor)".

Yet even before the start of the traditional 100-day

honeymoon between the newly elected Chief Executive and Philippine media,

Estrada was already embroiled in an ugly controversy, after giving the

go-signal for the burial of former President Marcos at the Libingan ng

mga Bayani (Heroes' Grave). Angering and galvanizing activists, civil

society groups and the human rights victims of the former dictator, Erap

soon relented after a series of mass actions and demonstrations in the

capital.

A year later, the Estrada government was again at

loggerheads with various progressive groups when Malacaņang tried to amend

the Constitution to allow foreign corporations to own land and media

establishments in the Philippines. Dubbed as CONCORD (Constitutional

Corrections for Reform and Development), the project was subsequently put

to the backburner after waves of protests and dipping presidential

popularity.

But learning his bag of tricks from the movie industry,

Erap soon made a big production a la Robert de Niro's Wag the Dog

to arrest his plunging approval rating. Using the breakdown of the

on-going peace-talks with the secessionist Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

as a justification, Estrada soon launched an all-out military offensive in

Mindanao, killing scores of people and damaging lives and property worth

millions. After overrunning the main rebel base Camp Abubakar, the

President and his hordes celebrated their victory by treating themselves

to a sumptuous feast of beer and lechon (roasted pork) as television

cameras recorded their gluttonous glee, to the consternation of civil

society leaders and to the indignation of the Muslim community.

though his punitive actions have nonetheless earned for

him a few popularity points, these were soon put to naught however with

the jueteng-gate scandal in October 2000, courtesy of former

presidential booze and Ilocos Sur Governor Luis "Chavit" Singson. Claiming

that the President has received P200 million in payola money from illegal

numbers game, Singson's expose triggered a series of demonstrations

demanding Estrada's resignation and impeachment trial that was televised

live from the Senate, transforming an otherwise esoteric legal proceeding

into the nation's leading telenovela.

It was under these circumstances that most celebrated

case of involuntary disappearance under the Estrada administration was

carried out, presumably by operatives of the Philippine National Police

(PNP) and the Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Task Force (PAOCTF). A

known PR Consultant and an estranged friend of Estrada, Salvador "Bubby"

Dacer and his driver Emmanuel Corbito were abducted on November 24, just

13 days prior to the formal opening of the impeachment trial, as he was

allegedly on the way to meet Erap's predecessor Fidel Ramos and hand over

vital documents that would prove the President's guilt. Though their

vehicle was soon found at the foot of a ravine in Maragondon, Cavite three

days after the abduction, their whereabouts remain a mystery up to this

day.

After the Rndgame: Qou Vadis?

While many have expected that the impeachment trial

would go until the 12th of February, no one foresaw that the entire

proceeding would come to an abrupt end on January 16, after the

administration-dominated Senate disallowed the opening of a sealed

enveloped allegedly containing bank records showing that Estrada had

indeed amassed P3.3 billion in a secrete account with Equitable PCI

Bank. With the populace suddenly losing confidence in the impeachment

proceedings, they spontaneously took to the streets that led to the Second

People Power Revolution.

While many have expected that the impeachment trial

would go until the 12th of February, no one foresaw that the entire

proceeding would come to an abrupt end on January 16, after the

administration-dominated Senate disallowed the opening of a sealed

enveloped allegedly containing bank records showing that Estrada had

indeed amassed P3.3 billion in a secrete account with Equitable PCI

Bank. With the populace suddenly losing confidence in the impeachment

proceedings, they spontaneously took to the streets that led to the Second

People Power Revolution.

As the crowd in EDSA (the site of the first People

Power Revolution in 1986) reached more than a million plus, with

simultaneous protest movements through out the country, the morale and

confidence of the military in their Commander-in-Chief began to

deteriorate, leading the Armed Forces top to brass to declare their

withdrawal of support to the administration on January19. By the following

day, Estrada left Malacaņang and his Vice-President and former

presidential daughter Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was sworn in as the

country's 14th President in an atmosphere reminiscent of Marcos' fall from

power 15 years ago.

yet, as the euphoria dies down the sense of

revolutionary upsurge begins to ebb away, the new government would have to

go to work and face the same pressing concerns that have been left in

total disarray by the previous administration. With 1,682 cases of

disappearances at the disposal of the courts, the petite, female

President would have to dig deep into the past in order to make a fresh

new start. For it would take earnestness , a sense of urgency and

doggedness in the search for justice and truth, more that a photogenic

face and a near reverent surname, to vanquish the poltergeists of the

past. Otherwise, the eerie silence that has since descended upon

Katipunan Road will remain forever oblivious to din and shouts of a

jubilant mob gathered at a stretch of cement and dirt called EDSA.

Civil society groups have also made significant

contributions in the over-all effort. The Families of Victims of

Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) for example, has been active in

data-gathering and in its numerous support programs. it also involved in

organizing forensic search missions in order to locate, identify and

recover the remains of the dead desaparecidos. Unfortunately, its

work has also been met by severe difficulties. Most often, witnesses are

fearful of coming out in the open lest they suffer from possible reprisal

from those responsible for the atrocities. There were also cases wherein

the victim's remains were removed from the burial site shortly before

exhumation.

Civil society groups have also made significant

contributions in the over-all effort. The Families of Victims of

Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) for example, has been active in

data-gathering and in its numerous support programs. it also involved in

organizing forensic search missions in order to locate, identify and

recover the remains of the dead desaparecidos. Unfortunately, its

work has also been met by severe difficulties. Most often, witnesses are

fearful of coming out in the open lest they suffer from possible reprisal

from those responsible for the atrocities. There were also cases wherein

the victim's remains were removed from the burial site shortly before

exhumation. While many have expected that the impeachment trial

would go until the 12th of February, no one foresaw that the entire

proceeding would come to an abrupt end on January 16, after the

administration-dominated Senate disallowed the opening of a sealed

enveloped allegedly containing bank records showing that Estrada had

indeed amassed P3.3 billion in a secrete account with Equitable PCI

Bank. With the populace suddenly losing confidence in the impeachment

proceedings, they spontaneously took to the streets that led to the Second

People Power Revolution.

While many have expected that the impeachment trial

would go until the 12th of February, no one foresaw that the entire

proceeding would come to an abrupt end on January 16, after the

administration-dominated Senate disallowed the opening of a sealed

enveloped allegedly containing bank records showing that Estrada had

indeed amassed P3.3 billion in a secrete account with Equitable PCI

Bank. With the populace suddenly losing confidence in the impeachment

proceedings, they spontaneously took to the streets that led to the Second

People Power Revolution.