As late as 1997, all of these would have been

unthinkable: an embattled Suharto stepping out of office; the mega-popular

Megawati Sukarnoputri elected to the Vice-Presidency; a near-sightless Gus

Dur giving an honest apology to the MPR (Permusyawaratan Rakyat /

People's Consultative Assembly); and an independent East Timor, with the

bearded Gusmao finally savoring the victory of national resistance. Events

have so unfolded in rapid successions that Indonesians would have to pinch

themselves to remind them that all these are for real, that the

nightmarish years of the New Order are definitely over. Indeed, the lead

-up to Suharto's fall was swift, intense and dramatic; generating a new

sense of hope for once-voiceless people. But like all periods of flux,

sudden changes not only foster great expectations, they also give birth to

the grandest illusions that are sometimes fraught with dangerous

implications.

As late as 1997, all of these would have been

unthinkable: an embattled Suharto stepping out of office; the mega-popular

Megawati Sukarnoputri elected to the Vice-Presidency; a near-sightless Gus

Dur giving an honest apology to the MPR (Permusyawaratan Rakyat /

People's Consultative Assembly); and an independent East Timor, with the

bearded Gusmao finally savoring the victory of national resistance. Events

have so unfolded in rapid successions that Indonesians would have to pinch

themselves to remind them that all these are for real, that the

nightmarish years of the New Order are definitely over. Indeed, the lead

-up to Suharto's fall was swift, intense and dramatic; generating a new

sense of hope for once-voiceless people. But like all periods of flux,

sudden changes not only foster great expectations, they also give birth to

the grandest illusions that are sometimes fraught with dangerous

implications.

As portraits of the former strongman are pulled

one-by-one from government offices and other public places, Indonesians

are beginning to entertain the idea that post-Suharto era would finally

introduce a break in the cycle of violence and patterns of disappearances

that have occurred in the past. With sudden burst of journalistic freedom

and the proliferation of myriad political parties, the public is slowly

seeing possible indications of democracy's future realization, pointing to

these events as augury of the things that are about to come.

Pundits, however, have argued that such optimism is

quite premature, for the new government would not only have to deal with

individual acts of impunity but would have to place itself in a directly

oppositional stance against interlinking system of political control. for

disappearances under the New Order were not carried out through isolated

actions of a few poorly disciplined officers but through the network of

institutions, ideological assumptions and standard operating procedures

which underlie State response to political dissent.

Under these circumstances, one must then hasten to ask:

is there a genuine room for hope and optimism? Is there a possibility that

the current regime could finally bring the perpetrators of involuntary

disappearances and other human rights abuses to justice? Does it have the

political will and wherewithal to do so? Or will it merely succumb to

further instability thus paving the way for greater communal strife and an

increasing number of desaparecidos?

Undercurrent for Repression

For most experts, the tragedy that was Indonesia

preceded Suharto's regime, even as it dates back to the struggle for

independence against the Dutch colonizers. Since its earliest stage, the

movement for national liberation was characterized by an overt reliance on

armed resistance and extra-legal struggle. By 1942, Indonesian nationalist

gained further confidence with the easy defeat of their colonial masters

in the hands of the Japanese. Sukarno, the country's first President,

declared independence on 17 August 1945, shortly after the surrender of

Japan and the eventual victory of the Allies. The country however, would

have to wait for another four years before it could finally gain total

freedom, after the final defeat and the subsequent withdrawal of the Dutch

colonial army.

The significant role played by the newly created army

during the time of the National Revolution, gradually paved the way for

its repeated intervention in political affairs. By the 1960s, the military

was already one of the major power players in Indonesian politics; the

others being Sukarno and the three-million strong PKI (Partai Komunis

Indonesia / Indonesian communist Party). The influence of the armed

forces was first demonstrated when in 1959, under pressure from the

general staff, Sukarno was forced to disband the Constituent Assembly and

nullify the 1950 Constitution in favor of the Charter earlier adopted in

1945, a move that effectively ended Indonesia's 15-year experiment with

constitutionalism and ensured the future curtailment of human rights.

The political role of the military was given further

justification through Pancasila - the official ideology of the Indonesian

State. This was first announced by President Sukarno in a speech delivered

on June 1945 to the Investigating Committee on Indonesian Independence and

contains five fundamental principles: (1) belief in the One Supreme God;

(2) just and civilized humanity; (3) unity of Indonesia; (4) deliberative

democracy; and (5) social justice. Enshrined in the Preamble of the 1945

Constitution is Pancasila's emphasis on the attainment of "key" national

goals such as national instability, security and order, which are often

times so fundamental that any threat to them is answered by "firm

measures" through the use of state violence. Moreover, despite official

rhetoric about democracy and political openness, it is the military and

the executive department that interpret and determine national goals and

priorities. Pancasila's emphasis on stability and security is usually used

to justify the curtailment of various civil liberties and political rights

and has provided the necessary legal facade to hide abuses perpetrated by

both the police and the military.

Through the years, the State has vigorously promoted

the Pancasila through strict and rigorous ideological conformity and

conditioning. Beginning in 1978, government employees from all ranks were

required to attend an obligatory Pancasila training activity dubbed as the

"Pancasila Indoctrination Course". in 1985, Law No. 8 was passed which

required all social organizations to adopt Pancasila as their sole

determining ideology. The law also provided severe penalties against any

criticism of or deviation from the State ideology. Due to its very

stringent measures, the law initially provoked an avalanche of protest

from various religious formations and human rights groups. Some of the

protesters were eventually arrested for subversion and meted lengthy

prison terms. Due to Pancasila's all-encompassing hold on all aspects of

social life, the widely-respected Far Eastern Economic Review was prompted

to note that the Indonesian government has become highly successful in

transforming the Pancasila from its "origin as a state philosophy,

expressing national Indonesian thinking, into a compulsory state ideology,

with operative value for those who are in power."

A Tragedy Begins to Unfold

Ironically, despite the myth of the military's

preeminent role in the country's pre-independence struggle, it was Suharto

(who was once a former officer in the Dutch colonial army) who was able to

exploit the military's political function to the fullest.

From its very inception, Suharto's New Order regime was

mired in bloodshed. On the pretext of curbing an impending coup by the PKI,

military operations were launched that eventually led to a bloodbath with

the number of PKI members and sympathizers murdered between 500,000 to one

million while another one million were illegally arrested and brought into

custody. Of those who were imprisoned, only 1,000 were formally charged in

court.

The military's intervention was justified under the

dwi fungsi (dual function) concept, wherein the role of the armed

forces is not limited to national defense but also serves as the nation's

primary guarantor of stability by carrying out various political, economic

and social responsibilities.

from then on, the military has become the

foremost powerhouse in Indonesian politics, with a strong representation

in the country's two legislative bodies - the People's Consultative

Assembly (MPR) and the People's Representative Council (DPR).

Moreover, its dual function was further given legal

credence through Law No. 20 entitled "the Fundamental Law for National

Defense and Security" which took effect in September 1982. As a result,

ABRI (Angkatan Bersanjata Republik Indonesia / Armed Forces of the

Republic of Indonesia) was given carte blanche authority to stifle

dissent and to ensure national security, often without due regard to legal

formalities.

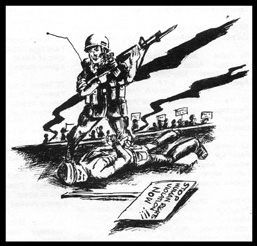

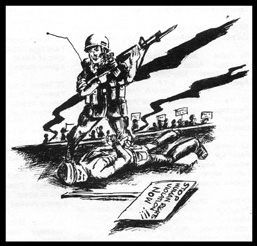

Declaring War on their Own People

In most instances, military impunity has usually been

exercised during anti-insurgency operations, most especially in regions

with strong and highly organized armed separatist movement. In Aceh for

example, situated in the northern tip of the island of Sumatra, ABRI

imposed a period of Military Operation Zone (DOM) from 1989 to 1998.

According to Support Committee for Human Rights in Aceh (SCHRA), this

highly stringent measure was responsible for the disappearance of

about 5,000 people; the killing of 3,000 others; and the rape of 128 women

and children. Aside from these, 23 mass graves were also discovered and

about 597 houses burnt. According to testimonies, these violations were

carried out by elements of the Army, the most notorious of which is the

Kopassus (army special forces) headed by Suharto's son-in-law Gen. Prabowo

Subianto.

Although the "disappearances" occurred within the

context of counter-insurgency operations, most of the victims as it turned

out, were neither members nor sympathizers of the rebel group GAM (Gerakan

Aceh Merdeka / Free Aceh movement) and disappeared while they were in

transit. In most cases, the victims were male, between 20 to 45 years old.

The situation is further aggravated by the lure of Aceh's rich natural

resources and the discovery of natural gas deposits in the Arun plain,

giving the central government in Jakarta added reason to further

consolidate its control over the region.

The lifting of the DOM, however, did not mark the end

of human rights abuses in the said region. from January to November of

last year, KontraS (Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan

/ Commission for Disappearances and Victims of Violence) has recorded 69

victims of disappearances, 167 cases of extra-judicial killings, 435

tortured detainees, and 312 cases of arbitrary detention.

The lifting of the DOM, however, did not mark the end

of human rights abuses in the said region. from January to November of

last year, KontraS (Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan

/ Commission for Disappearances and Victims of Violence) has recorded 69

victims of disappearances, 167 cases of extra-judicial killings, 435

tortured detainees, and 312 cases of arbitrary detention.

Under the New Order, 23 cases of students

disappearances were also recorded from 1996 to 1998. Most o0f those who

resurfaced told tales of torture, intimidation and threats of punitive

action if ever they would publicly divulge their experiences with their

captors.

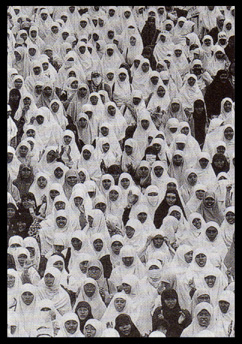

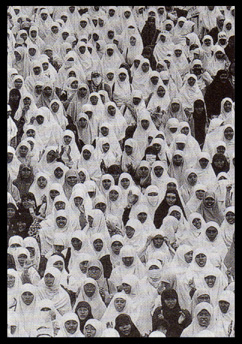

The military was also blamed for the highly

controversial Tanjung Priok massacre of 12 September 1984. Based on

available documentation, the bloodbath occurred after the military

provoked and shot the participants in a Koran-reading activity. In the

ensuing melee, hundreds were killed and 15 persons were reported "missing"

and unaccounted for.

Over the past ten years, an estimated 15,000 people

have already disappeared, most of them from the troubled spots of Aceh,

the former province of East Timor and former Irian Jaya. In West Papua

alone, 5 cases of extra-judicial killings were reported for the first time

11 months of the year 2000 perpetrated allegedly by the military;

including 9 cases of torture and maltreatment, and 29 individual cases of

arbitrary detention.

Old Boys Mentality

In July 1998, ABRI admitted the involvement of 11

of its men in the kidnapping and torture of opportunists. This led to

Prabowo's replacement by Gen. Muchdi Purwopranyoto as Koppasus chief. Its

head of intelligence, Col. Chairawan was also removed from his post though

he was still retained in the service. Despite the militay's admission,

ABRI spokeperson Maj. Gen. Syasmul Ma'arif sought to deodorize the guilt

of his fellow mistah by saying that what they have committed were not

heinous in nature but merely "procedural errors" in the accomplishment of

their duties. to make matters worse, the perpetrators were only given

slaps in the wrists, with a court ruling of 12 to 22 months imprisonment.

traditionally, military violators of human rights are never given harsh

punishments for their actions. Oppositionists, on the other hand, are

"normally" handed out severe penalties for even the slightest

offenses.

But such actions, however, is not an isolated case. As

proven time and again, the military tends to take care of its own members

prohibiting them to owe up to the crimes that they have committed.

It is thus no wonder that despite the fall of Suharto,

this "old boys mentality" within the military has become the biggest

stumbling block in the pursuit of justice. As long as this mindset is not

dismantled, the post-Suharto Indonesia will not be different from the

"old" New Order that it has replaced.

As late as 1997, all of these would have been

unthinkable: an embattled Suharto stepping out of office; the mega-popular

Megawati Sukarnoputri elected to the Vice-Presidency; a near-sightless Gus

Dur giving an honest apology to the MPR (Permusyawaratan Rakyat /

People's Consultative Assembly); and an independent East Timor, with the

bearded Gusmao finally savoring the victory of national resistance. Events

have so unfolded in rapid successions that Indonesians would have to pinch

themselves to remind them that all these are for real, that the

nightmarish years of the New Order are definitely over. Indeed, the lead

-up to Suharto's fall was swift, intense and dramatic; generating a new

sense of hope for once-voiceless people. But like all periods of flux,

sudden changes not only foster great expectations, they also give birth to

the grandest illusions that are sometimes fraught with dangerous

implications.

As late as 1997, all of these would have been

unthinkable: an embattled Suharto stepping out of office; the mega-popular

Megawati Sukarnoputri elected to the Vice-Presidency; a near-sightless Gus

Dur giving an honest apology to the MPR (Permusyawaratan Rakyat /

People's Consultative Assembly); and an independent East Timor, with the

bearded Gusmao finally savoring the victory of national resistance. Events

have so unfolded in rapid successions that Indonesians would have to pinch

themselves to remind them that all these are for real, that the

nightmarish years of the New Order are definitely over. Indeed, the lead

-up to Suharto's fall was swift, intense and dramatic; generating a new

sense of hope for once-voiceless people. But like all periods of flux,

sudden changes not only foster great expectations, they also give birth to

the grandest illusions that are sometimes fraught with dangerous

implications. The lifting of the DOM, however, did not mark the end

of human rights abuses in the said region. from January to November of

last year, KontraS (Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan

/ Commission for Disappearances and Victims of Violence) has recorded 69

victims of disappearances, 167 cases of extra-judicial killings, 435

tortured detainees, and 312 cases of arbitrary detention.

The lifting of the DOM, however, did not mark the end

of human rights abuses in the said region. from January to November of

last year, KontraS (Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan

/ Commission for Disappearances and Victims of Violence) has recorded 69

victims of disappearances, 167 cases of extra-judicial killings, 435

tortured detainees, and 312 cases of arbitrary detention.