UNSILENCED : A REVIEW

by Alan Harmer

The Evening of 14 October 2000

It was a happy festive evening, gay with songs and laughter. The small

village of Sta. Maria was celebrating its annual fiesta. The central

square was alive with the lights and sounds of games, pop music,

amusement stands and side shows. Delicious smells of aromatic spices and

fresh fried pork wafted into the night air. Everyone was outside

enjoying themselves.

14 October 2000 - An evening that some people will have engraved in

their memory forever…

Sta. Maria is a small community located in the Trento province along the

Pan Philippine highway, that majestic road that cuts its way north-south

across the whole island of Mindanao, in the south of the Philippines. In

the middle of the island, in Trento, the road runs through lush tropical

forest passing the beautiful Agusan marsh wild life sanctuary. It is a

remote region, a relatively poor area, and lack of reliable water

supplies often spreads disease among the indigenous population. The main

employer in the region, apart from the local agriculture is the logging

operation, PICOP (the American-owned, Paper Industries Cooperation of

the Philippines) with 2,000 employees in the area. Their logging lorries

are to be seen frequently, rumbling along the main highway, taking their

precious load of tree trunks down to the factory for processing.

Adjoining the village of Sta. Maria is an army camp, which houses part

of the 62nd Infantry Battalion. There is often agitation with the NPA,

the New People’s Army, and only two weeks earlier, the battalion

commander, Colonel Velasco, had been ambushed and killed by NPA1 militia

from Talacogon, 6 villages away.

In the village square, the crowd was becoming denser by the minute.

Sporting a gleaming white shirt and with his hair especially spruced up

for the evening, Crispin Barot was out looking for his six friends,

Romualdo, Jovencio, Arnold, Joseph, Diosdado and Artemio. A young man of

18 years old, Crispin lived in Sta Maria and worked for PICOP. Through

working in the logging company, he had met these close friends, who came

from the neighboring town of Bunawan.

There they were in the crowd! They greeted one another happily. Laughing

and joking together, they moved out of the village square and drifted

slowly down the road to Jumapoy Joint, a favorite meeting place. The

crowded videoke bar was packed to bursting, almost impossible to enter.

They joined the crowd outside of more than fifty people, dancing and

listening to the loud pop music beaming from the loudspeakers. Suddenly,

a soldier in army uniform accosted Romualdo.

“You are a member of the NPA.”

“I’m sorry I don’t understand,” said Romualdo. “I recognize your face.

You were involved in the killing of Colonel Velasco. Come with me.”

“You must be mistaken,” he said “I’ve got nothing to do with the NPA.”

“He’s not with the NPA,” joined in his friends.

“He’s from our village, we know him well.”

But the soldier produced a pistol, pointed it at Romualdo and pushed him

out to the edge of the crowd. His friends followed. The soldier took him

roughly by the arm and forced him down the road, frog-marched him with

the pistol in his back. His five friends followed, protesting, “It’s not

him.” Crispin went along behind. He was scared and hung back. Other

soldiers, some in uniform, some armed, joined in and herded the six

young men towards the army camp, only a short distance down the road.

Crispin watched dismayed as his friends went through the main gates,

uncertain what to do; just then his uncle pulled him away and told him

not to venture into the army camp but to go home.

Where did the young men disappear to?

The

following day, the young men had not returned to their village. Their

families started wondering why they were not back home. Crispin

recounted how they had been marched to the army camp and had been taken

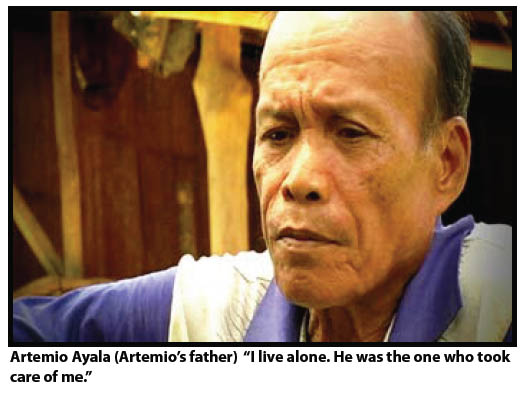

inside. Two people from the families, Artemio Ayala and Macaria Legare

immediately went off to the camp to find out what had happened. They

were not allowed in. Others members of the family went there, the

mothers of the young men, in tears, but all were turned away roughly, or

barred at the gate. Finally, six days later, a delegation of the parents

accompanied by the mayor of their village, the vice-mayor and a barangay

captain went to the army camp requesting to speak to the commanding

officer. They were allowed in but the army denied anything to do with

the young men. The families were shown round the camp. There was no

trace of their lost sons. Crispin Barot and the families of the missing

men made written statements with the local police. The military

continued to deny any involvement and all knowledge of the whereabouts

of the young men.

The

following day, the young men had not returned to their village. Their

families started wondering why they were not back home. Crispin

recounted how they had been marched to the army camp and had been taken

inside. Two people from the families, Artemio Ayala and Macaria Legare

immediately went off to the camp to find out what had happened. They

were not allowed in. Others members of the family went there, the

mothers of the young men, in tears, but all were turned away roughly, or

barred at the gate. Finally, six days later, a delegation of the parents

accompanied by the mayor of their village, the vice-mayor and a barangay

captain went to the army camp requesting to speak to the commanding

officer. They were allowed in but the army denied anything to do with

the young men. The families were shown round the camp. There was no

trace of their lost sons. Crispin Barot and the families of the missing

men made written statements with the local police. The military

continued to deny any involvement and all knowledge of the whereabouts

of the young men.

This is the point at which most accounts about disappearances come to an

abrupt end.

In not knowing what happens to the people who disappear;

In the blanket denial of the military, the police, and government

officials to admit anything;

In the refusal of the authorities to investigate the case;

In the lack of witnesses because they are scared to come forward and

disclose any information;

In the forgotten tragedies of the individual families;

In the terrible pain of the memories of those who are missing;

In the unresolved loss and grief…

This is normally where such tragic histories end.

The Film, UNSILENCED

The scene opens with the magnificent scenery of the Trento province,

dense green forests, palm trees waving in the wind and the broad

fast-running river. The ordinary life of the villagers, their simple

routine, their attractive faces…

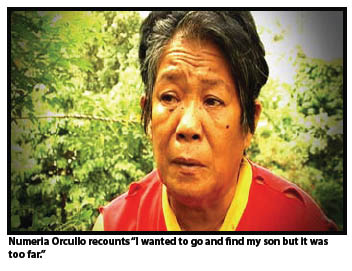

Numeria Orcullo says “It is a simple life here, we are a peaceful

people.”

The families go on to talk about their sons, and the work they did in

the logging company. Then they hear the news, their disbelief that the

young men are really missing, the panic and the fear.

Numeria Orculla recounts, after she was told her son was missing “I

wanted to go and find him but it was too far. I am not familiar with

that place.”

Later on, with the other families desperately trying to trace the young

men, “We searched for them on foot, day and night, for a week…”

She tried hard to gain access to the army camp. In tears, she describes

her treatment at the ruthless hands of the army. Here, in a few simple

images and a few simple words is the whole tragedy of disappearances.

Seeking Justice

There, the tragedy might have ended had it not been for FIND (Families

of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance) who read about the incident in

the local paper: Rose Deano from FIND visited the families of the young

men. It needed several visits to gain their confidence, and to insist on

the importance of action, and to reassure them that they would be helped

in their cause. With the support of FIND, the families filed a court

case against the army.

The initial hearing in the court was rejected.

However, four years later, an important witness emerged. Exequias

Doyugan, an army sergeant, had witnessed at first hand the killing of

the young men but had chosen to remain silent, afraid that he would be

killed. At 41 years old, he had been in the army since 1988. He left in

2007. With encouragement from FIND, he resolved to speak out. The army

discovered this, and in August 2007, an envoy on behalf of the Captain

of the 4th Infantry Battalion tried to persuade him to rejoin the army

and offered him 200,000 pesos to remain silent. Doyugan decided, with

strong backing from FIND, to tell the truth.

A court case was filed in the Regional Court at Prosperidad, Agusan del

Sur, against Corporal Rodrigo Billones, the army soldier who had

arrested Romualdo and brought him to the army camp. He was easily

identified by Crispin Barot and others as the person initially

responsible for abducting the young men.

In

court, Doyugan, as key witness, said that on the night of the killings,

the army camp was very quiet. Many of the soldiers had gone to the

village fiesta. The commanding officer, Colonel Cabando, was away from

the camp. Doyugan overheard a telephone conversation between the camp

Senior Officer and Cabando telling him that they had found some possible

members of the NPA. Cabando said that they should kill the suspects. The

young men entered the camp, they were tied with rope and manhandled by a

number of soldiers. One of the soldiers struck Arnoldo on the head with

an iron pipe. Three other soldiers joined in and together they beat the

six young men to death. The soldiers dug graves at the back of the

extension building and buried the bodies. However, three days later,

they dug them up and took them away in a Chevrolet service vehicle to a

point along the road in Trento and burned the corpses there. Doyugan

said that Billones had nothing to do with the killing, the digging up of

the corpses and the burning.

In

court, Doyugan, as key witness, said that on the night of the killings,

the army camp was very quiet. Many of the soldiers had gone to the

village fiesta. The commanding officer, Colonel Cabando, was away from

the camp. Doyugan overheard a telephone conversation between the camp

Senior Officer and Cabando telling him that they had found some possible

members of the NPA. Cabando said that they should kill the suspects. The

young men entered the camp, they were tied with rope and manhandled by a

number of soldiers. One of the soldiers struck Arnoldo on the head with

an iron pipe. Three other soldiers joined in and together they beat the

six young men to death. The soldiers dug graves at the back of the

extension building and buried the bodies. However, three days later,

they dug them up and took them away in a Chevrolet service vehicle to a

point along the road in Trento and burned the corpses there. Doyugan

said that Billones had nothing to do with the killing, the digging up of

the corpses and the burning.

The case was judged on 11 July 2008. Corporal Rodrigo Billones was

convicted for unlawful arrest and illegal detention of the 6 men. He was

sentenced to a maximum of 15 years imprisonment. The other army

personnel, officers and soldiers in the crime are now being

investigated.

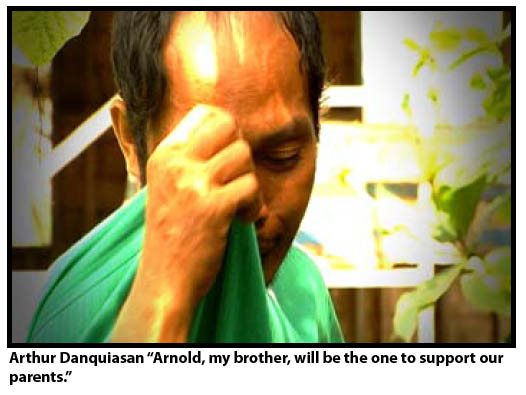

The Victims

The six men from Bunawan village, who disappeared, were:

Romualdo Orcullo (27 years old)

Arnold Dangquiasan (29 years old)

Joseph Belar (31 years old)

Diosdado Oliver (30 years old)

Artemio Ayala (29 years old)

Jovencio Legare (41 years old)

A Landmark Case

Nilda

Sevilla, Chairperson of FIND, says “The PICOP case is unique in the

sense that it is a landmark victory in court with the conviction of the

accused army corporal as accomplice to the crime of kidnapping and

serious illegal detention of the six paper factory workers. But what is

more important is the conviction of the principals, the military men and

members of the 62nd infantry battalion. Now they have filed a case

before the office of the prosecutor in Agusan for multiple murder,

serious illegal detention, coercion and torture. These are existing

crimes punishable under the Revised Penal Code.”

Nilda

Sevilla, Chairperson of FIND, says “The PICOP case is unique in the

sense that it is a landmark victory in court with the conviction of the

accused army corporal as accomplice to the crime of kidnapping and

serious illegal detention of the six paper factory workers. But what is

more important is the conviction of the principals, the military men and

members of the 62nd infantry battalion. Now they have filed a case

before the office of the prosecutor in Agusan for multiple murder,

serious illegal detention, coercion and torture. These are existing

crimes punishable under the Revised Penal Code.”

“However not one of these crimes captures all the elements of enforced

disappearance, especially the element of concealment, of the fate and

whereabouts of the victim. So enforced disappearance is enforced

disappearance; it is not kidnapping and illegal detention. What is

important is for the phenomenon of Enforced Disappearance to end.”

The Need for Government Laws against Enforced Disappearances

The documentary film is a joint production between FIND and AFAD. It is

valuable in detailing the whole story of the PICOP case: the abduction

of the six men, the disappearance, and the killing. It interviews the

families of the disappeared. It recounts the actions of the families

taken against the army and the resulting successful court case.

The main conclusion is that it is vital for the Philippine government to

ratify the International Convention against Enforced Disappearance and

to enact local laws to guarantee security for all their citizens and

justice to eliminate Enforced Disappearances.

The film is available from the AFAD office, Rooms 310-311 Philippine

Social Science Center, Commonwealth Ave., Diliman, Quezon City,

Philippines and in the AFAD website:

www.afad-online.org

(Click

here to watch movie)

Alan Harmer is a human-rights supporter in Geneva. Over the last twelve

years he has been host to members and friends from AFAD who come to

participate in meetings at the United Nations.