UNWGEID and the 1992 UN Declaration on Disappearances

Abridged

Version of the Speech of Ms. Mandira Sharma delivered during the 30th

Anniversary of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances 5 November 2010

Abridged

Version of the Speech of Ms. Mandira Sharma delivered during the 30th

Anniversary of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances 5 November 2010

Chairperson, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I have been asked to speak about the United Nations Working Group on

Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UN WGEID) and the 1992 UN

Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced or

Involuntary Disappearances (the Declaration). Now that we are all

expecting the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance (The Convention) to come into force, I feel

like giving a eulogy. But this would be entirely wrong, as I strongly

believe that the Declaration lives on in the Convention and in the day

to day practice of numerous human rights defenders around the world. I

believe the WGEID and the Declaration have done a great service to human

rights over the last three decades, for which we are all very grateful.

I particularly want to salute the WGEID’s practice of adopting General

Comments on the Declaration, which have assisted us time and again to

more forcefully advocate for specific measures for the prevention,

investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of enforced disappearances

which are to be taken by governments.

To demonstrate my point, I would like to focus on just one specific

article in the Declaration which I know my colleagues in Nepal, as well

as friends and human rights defenders in the rest of Asia, have found

tremendously helpful. This is Article 17 and the General Comments of

2000 relating to it. The way in which the Declaration and the WGEID in

its General Comment explicitly define disappearances as “a continuing

offence” is something for which many lawyers and relatives of the

disappeared are indebted to.

In Asia, before the WGEID was established and before the Declaration

came into being, we always thought of disappearances as a Latin American

phenomenon. This is not because disappearances were not happening in

Asia, but we did not characterize them as a regional phenomenon. Thanks

to the WGEID and the Declaration that we were able to highlight our

concerns more strongly and name them as among the most egregious

violations of human rights.

We felt the need for organizing ourselves and expose the patterns of

disappearance in Asia by forming the Asian Federation Against

Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD). Solidarity with similar associations

in other regions such as FEDEFAM, FEMED, We Remember Belarus has

given us the strength to continue our struggle in establishing truth and

attaining justice. Together under the International Coalition Against

Enforced Disappearance (ICAED), we continue to campaign for the

ratification of the Convention. In the course of this work, we lost one

of our colleagues, Patricio Rice, who was the focal person of ICAED.

The practice of disappearance is not a past phenomenon in Asia. It has

continued up to this date. The AFAD continues to receive cases of

ongoing disappearance from Southern Thailand, Northern part of

Philippines, Kashmir, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In addition to this, we

continue to struggle for establishing the truth of disappearance that

took place years ago. More than 60,000 people are thought to have

disappeared over the past two decades, both in the context of the war

with the Tamil Tigers and during the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna

insurrection of the late 1980s. The fact that the Working Group visited

Sri Lanka three times and raised concerns about these violations has,

from the outset, made it impossible for the government to deny knowledge

of disappearances in the country. In India, hundreds are known to have

disappeared in Punjab as well as in Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh, the

Northeast and, most recently, in Chhattisgarh. Since the peak of the

insurgency in Kashmir in 1989, some 8,000 people have reported to be

disappeared at the hands of Indian security forces. Last year, the

Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) published a report

about 2,900 mass graves in 18 villages near the line of control,

dividing Kashmir between India and Pakistan.

We

are very much helped by the continuing work of the WGEID in relation to

these cases in the region. In Nepal, particularly, we, human rights

defenders and the families of the disappeared were very much helped by

the work of the WGEID. Having the Group’s reporting to the then

Commission on Human Rights in both 2003 and 2004 that Nepal had the

highest number of disappearances firmly placed the situation in my

country on the international community’s agenda. It has become a serious

embarrassment to the government. It certainly also helped us to advocate

for the establishment of an Office of the High Commissioner for Human

Rights (OHCHR). As the UN became involved in the crisis in Nepal, the

number of human rights violations notably decreased. The OHCHR’s field

presence in the country since May 2005 continues to give immediate

positive impact on our human rights situation, as evidenced by the

decrease in the number of disappearances and extrajudicial executions in

Nepal.

We

are very much helped by the continuing work of the WGEID in relation to

these cases in the region. In Nepal, particularly, we, human rights

defenders and the families of the disappeared were very much helped by

the work of the WGEID. Having the Group’s reporting to the then

Commission on Human Rights in both 2003 and 2004 that Nepal had the

highest number of disappearances firmly placed the situation in my

country on the international community’s agenda. It has become a serious

embarrassment to the government. It certainly also helped us to advocate

for the establishment of an Office of the High Commissioner for Human

Rights (OHCHR). As the UN became involved in the crisis in Nepal, the

number of human rights violations notably decreased. The OHCHR’s field

presence in the country since May 2005 continues to give immediate

positive impact on our human rights situation, as evidenced by the

decrease in the number of disappearances and extrajudicial executions in

Nepal.

We also found the visit by the WGEID in December 2004 to be extremely

helpful. The recommendations in the subsequent report remain invaluable

to us up to this day. For instance, the WGEID recommended that the

Supreme Court consider a more active application of its inherent

contempt power to hold accountable and punish officials who are not

truthful before the Court. Regardless of its more robust performance

since the end of the conflict, the Supreme Court bears considerable

responsibility for not setting strict limits on state behavior during

the period of the armed conflict. We thank the WGEID for highlighting

this shortcoming. Weak sanctions for perjury and contempt of court in

law exacerbate the problem. But as the WGEID said, the court has

inherent powers that it should use more actively. Despite obvious and

repeated lies and misinformation from the security forces and government

authorities, no one has ever been prosecuted or otherwise disciplined by

the courts for perjury. This contributes to the prevailing sense among

security forces that they are above the law and of course reinforces the

prevailing impunity.

There are, however, some positive signs. In June 2007, Nepal’s Supreme

Court ruled on 83 habeas corpus writs, and ordered the government to

immediately set up a commission of inquiry to investigate all

allegations of enforced disappearances and to provide interim relief to

the relatives of the victims. The court ordered that the Commission of

Inquiry must comply with international human rights standards. However,

to date, this order to set up a commission of inquiry has not been

implemented. The Supreme Court and courts of appeal have also repeatedly

ordered police and public prosecutors to investigate individual

complaints of disappearances and other violations from the conflict

period. Quite recently, the Supreme Court imposed legal strictures on

the Nepal Police and Attorney General’s Department (as institutions) for

their lack of rigor in investigations. The police and other authorities,

however, are still not complying with court orders. Even if the

punishment itself is little more than symbolic, I would argue that it

will have considerable impact.

Allow me now to focus in more detail on Article 17 of the Declaration,

which as you all know, says that “Acts constituting enforced

disappearance shall be considered continuing offence as long as the

perpetrators continue to conceal the fate and the whereabouts of persons

who have disappeared and these facts remain unclarified.”

As explained by the WGEID in its General Comment of 2000, the definition

of “continuing offence” is of crucial importance for establishing

the responsibilities of State authorities. The article is intended to

prevent States from reneging on their duty to provide full redress to

the families of the disappeared, including by explicitly ruling out that

perpetrators of those criminal acts take advantage of statutes of

limitations. This goes to the heart of the human rights problems in

Nepal and so many other countries – that of widespread and systematic

impunity. We are fighting to have those responsible brought to justice,

but face considerable hurdles, both in law and in practice.

As of today, all Asian countries lack legislation criminalizing

disappearances. For several years now, we have been pushing governments

to put in place such legislation, and set out procedures for

investigations that will both identify and punish those responsible and

also result in the release of the disappeared person, if alive, or the

return of their body and reparation for victims of enforced

disappearance who are subsequently released and for their families who

have to suffer so much due to the uncertainty and anguish that

disappearances cause.

In Nepal, we are also advocating for a commission of inquiry into

disappearances, as provided for in the peace agreement of 2006. We do

not see this as a substitute to what I have just discussed and we are

only pushing for it provided it conforms to international standards. The

initial draft was extremely problematic, with the definition of

disappearances falling far short from the one in the Convention. It has

now been changed subsequently because of the pressures from the civil

society and the family members of disappeared persons. A new version of

the bill is currently filed before the Legislative Committee of the

Parliament. This also has some problems such as the provision that

complaints will have to be filed within six months of the promulgation

of the Act. To strengthen our position, we have been working with the

members of the Parliament to have this provision amended and have been

able to draw on the work of WGEID and the provisions of the Declaration,

its General Comments and the Convention. Whether or not we will be

successful remains to be seen.

Similarly, following extensive criticisms from civil society and the

international community, the Peace and Reconstruction Ministry has

reviewed a bill to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission which

had initially provided for the possibility of amnesty for a wide range

of crimes, including crimes against humanity. We were able to get these

provisions amended, and though amnesty is still provided for in the

Bill, it is now explicitly ruled out for grave human rights violations

including disappearances.

We have some way to go before both these commissions will be set up, and

have to practice extreme vigilance to avoid some people in Nepal using

the concept of reconciliation to prevent meaningful investigations into

violations and/or abuses committed both by the Maoists and the security

forces.

We all hope that the Convention and the Committee on Enforced

Disappearances that will monitor state compliance of the treaty will be

able to be as innovative as the WG has been and continues to be. In

particular, we believe that the Convention will be a strong tool to

break through the climate of impunity. It will be important to not only

consider prosecutions as such but consider a wider range of innovative

measures that can be taken to address this evil.

Working in the field, we see a huge gap between standards and practice.

How to mitigate this gap in realizing the right not to be disappeared

requires proactive, sustained and creative ways of engaging with state

agencies. Increasingly, non-state actors (such as the Maoists in Nepal)

are involved in abductions and disappearances and the State is too weak

to address these. We need to make sure that they are also held to

account.

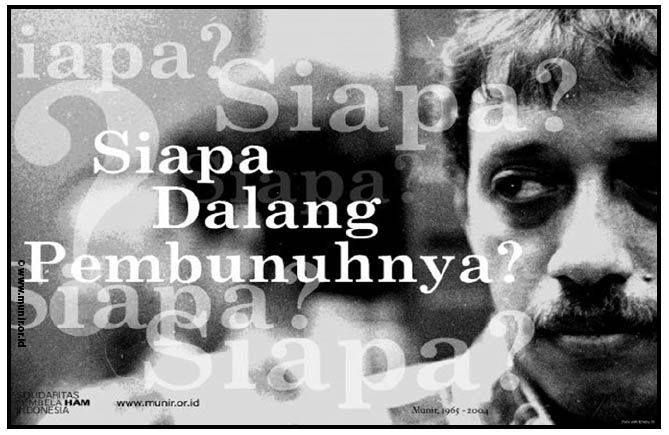

Threat to human rights defenders, families of disappeared person is

another aspect that we need to respond to. The case of Munir, former

Chairperson of the AFAD, is emblematic to what human rights defenders

face on the ground….

Thank you.

Mandira Sharma is currently the Executive Director of Advocacy

Forum-Nepal, a leading human rights organization in Nepal, and incumbent

Treasurer of the AFAD. Ms Sharma has carved a niche in the Nepalese

human rights arena and has been at the forefront of human rights

advocacy in Nepal since past 15 years. Ms Sharma is a recipient of many

awards including “Human Rights Defender Award” from Human Rights Watch.