As the newly-produced bill was also weak and full of

loopholes, a group of human rights organizations, including

Accountability Watch Committee (AWC), Advocacy Forum (AF), Amnesty

International (AI), Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances

(AFAD), Human Rights Watch (HRW), International Center for Transitional

Justice (ICTJ), International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and Informal

Sector Service Center (INSEC) submitted a joint memorandum to Peace

Minister Rakam Chemjong regarding some critical amendments to be made in

the latest draft bill on the formation of a commission on disappearance

at the latter’s ministerial residence at Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk, in

the early hours of the morning on 30 August 2009. The memo submission

event was timed to coincide with the International Day of the

Disappeared.

To make the legislation on disappearance in line with

the Supreme Court verdict of 1 July 2007 and relevant international

standards, the memo stressed on a host of amendments including: .

Defining ‘enforced disappearance’ consistently with the internationally

recognized definition and recognizing that, under some circumstances,

the act of enforced disappearance amounts to a crime against humanity;

• Defining the modes of individual criminal liability,

including responsibility of superiors and subordinates, consistently

with internationally accepted legal standards;

• Establishing a minimum and a maximum penalty for the crime

of enforced disappearance as such and for the crime of enforced

disappearance as a crime against humanity;

• Ensuring the independence, impartiality and competence of

the Commission of Inquiry into enforced disappearances;

• Ensuring that the Commission of Inquiry into enforced

disappearances is granted the powers and means to be able to effectively

fulfill its mandate;

• Ensuring that all aspects of the work of the

Commission of Inquiry into enforced disappearances respect, protect and

promote the rights of victims, witnesses and alleged perpetrators;

• Ensuring that the recommendations of the Commission of

Inquiry are made public and implemented.

Following

the submission, the Peace Ministry acted promptly and incorporated some

of the suggestions put forward by the human rights organizations. The

ministry also convened a consultation with human rights organizations to

discuss the new bill. During the discussions, the issue of "definition,"

"statutory limits" and "implementation of the commission’s

recommendations" featured significantly. Questions were raised why the

government is hesitating to define "disappearances" in line with the

article of the 2006 UN Convention For the Protection of All Persons from

Enforced Disappearance and the article 7(2) (i) of the Rome Statute of

the International Criminal Court as suggested by the rights

organizations in their memorandum. Similarly, there was much uproar visà-

vis the statutes of limitation as the new revised bill also failed to

regard "disappearance" as a continuing crime. Also the discussions

focused on ensuring the effective implementation of the recommendations

of the commission, in the absence of which the entire process would turn

out to be a sheer anticlimax. The representatives of the Peace Ministry

assured that they would make the necessary changes as suggested by the

participants but were yet to produce the re-revised bill.

Following

the submission, the Peace Ministry acted promptly and incorporated some

of the suggestions put forward by the human rights organizations. The

ministry also convened a consultation with human rights organizations to

discuss the new bill. During the discussions, the issue of "definition,"

"statutory limits" and "implementation of the commission’s

recommendations" featured significantly. Questions were raised why the

government is hesitating to define "disappearances" in line with the

article of the 2006 UN Convention For the Protection of All Persons from

Enforced Disappearance and the article 7(2) (i) of the Rome Statute of

the International Criminal Court as suggested by the rights

organizations in their memorandum. Similarly, there was much uproar visà-

vis the statutes of limitation as the new revised bill also failed to

regard "disappearance" as a continuing crime. Also the discussions

focused on ensuring the effective implementation of the recommendations

of the commission, in the absence of which the entire process would turn

out to be a sheer anticlimax. The representatives of the Peace Ministry

assured that they would make the necessary changes as suggested by the

participants but were yet to produce the re-revised bill.

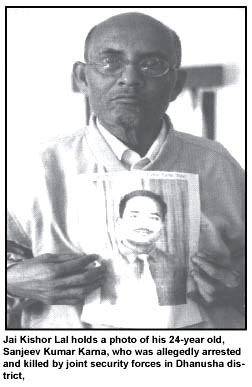

The family members of the victims and the human

rights defenders all still waiting with their finger crossed for

possible developments regarding the formation of the commission. Like

the victims who are wading through the mire of injustice and state

indifference with hope against hope for justice, redress and reunion

with their loved ones, we, the human rights advocates, despite endless

frustrations and unforeseen impediments, are marching forward with a

torch of justice in our hand resounding the glossed-up dictum that

"Droit Ne Poet Pas Morier et disparaître" (RightsCannot Die &

Disappear).

______________________________

1 The Supreme Court’s verdict held

that that the existing legal framework related to commissions of inquiry

is inadequate to address the cases of disappearance that were

systematically practiced during the armed conflict in Nepal. The order

gave directives to the interim Government to introduce a new legislation

to ensure the establishment of a credible, competent, impartial and

fully independent commission. The order also stated that, in doing so,

the Interim Government should take into account the Convention for the

Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and the criteria

for Commissions of Inquiry developed by the United Nations Office of

High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Dhiraj

Kumar Pokhel. A human rights advocate, Dhiraj works as focal person

of Advocacy Forum-Nepal for the AFAD.