|

UP

MIDDLE

DOWN

PDF

DOWNLOAD

CONTENTS

COVER

Editorial

Letter to the Editor

Cover Story

On the Road to Ratification

News Features

Half Widows and Orphans–A Way Forward in Islamic

Jurisprudence

Toward a Genuine Human Rights Movement of the

Victims of Human Rights Violations

The Five-Year Old Munir Case

Rights Cannot Die and Disappear

MIDDLE

Celebrating Human Rights Through Poetry and Music

UP

MIDDLE

DOWN

Voice from Thailand Calling for the Convention Now

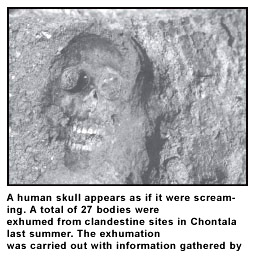

The First Asian Conference on Psychosocial Work in

the Search for Enforced Disappeared Persons, in Exhumation Processes and the

Struggle for Justice and Truth

Missing Justice: Impunity and the Long Shadow of

War

On Latin America

Guatemala: First Steps to End Impunity

Human Rights Trials in Argentina

Reflections from the Secretariat

Initial Breakthroughs in India

The Power of Memory: A Reflection

Reclaiming our Dignity,Reasserting our Rights

UP

MIDDLE

DOWN

Press Release

Buried Evidence: Unknown,Unmarked Mass Graves in

Indian-Administered Kashmir, A Preliminary Report

Urgent Appeal

Review

Mrs. B: A Review

Minds Teasers

Crossword Puzzle

CryptoQuote

Literary Corner

Emptiness

AFAD MEMBER- ORGANIZATIONS

UP

MIDDLE

DOWN

|

ON LATIN AMERICA

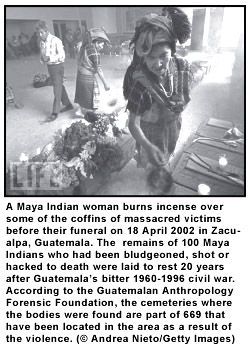

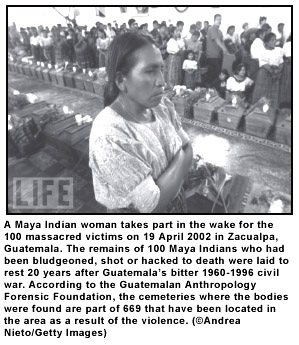

Guatemala : First Steps to End Impunity Over 45,000 Cases of Enforced

Disappearance by

Atty. Gabriella Citroni

Introduction

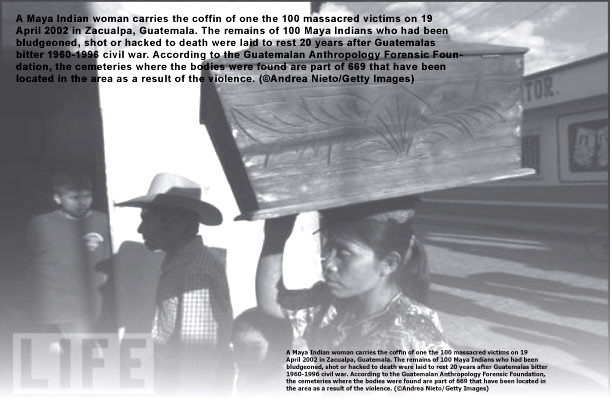

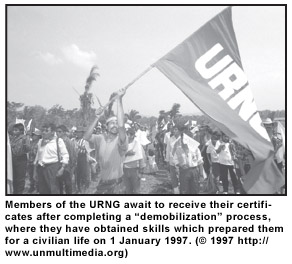

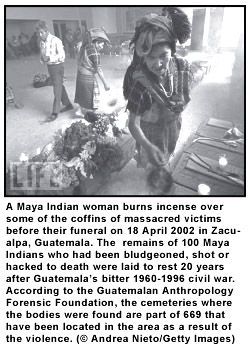

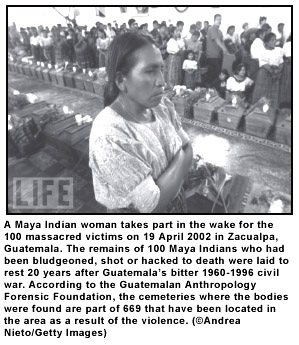

From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala was ravaged by a bloody

internal armed conflict, which left almost 250,000 people arbitrarily

killed, around one million of refugees and internally displaced people

and 45,000 victims of enforced disappearance. The great majority of

victims belonged to the Mayan population.1

The conflict from which disappearances arose in

Guatemala began in the sixties when a small group of young army officers

rebelled against the military government, accusing it of corruption. The

rebellion was put down, and the young officers fled to the mountains of

eastern Guatemala where they began a guerrilla war. These guerrillas

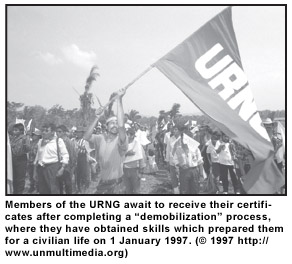

soon turned into a Marxist movement (URNG – Unidad

Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca) whose objective was to

overthrow the government and take power. It is important to highlight

that the Guatemalan armed conflict occurred in the framework of the Cold

War2. On 29 December 1996, the government and the URNG signed an

Agreement on a Firm and Lasting Peace.

3

The final report presented in 1999 by the Guatemalan

Truth Commission4 known as

"Commission for Historical Clarification" concluded that:

In Guatemala, forced disappearance was a systematic

practice which, in nearly all cases, was the result of intelligence

operations. The objective was to disarticulate the movements or

organizations identified by the State as favorable to the insurgency,

as well as to spread terror among the people. The victims of these

disappearances were peasants, social and student leaders, professors,

political leaders, members of religious communities and priests, and

even members of military or paramilitary organizations that fell under

the suspicion of collaborating with the enemy. Those responsible for

these forced disappearances violated fundamental human rights.5

[…] The ultimate scope of enforced disappearance of persons is the

destruction of something - an organization, the diffusion of a

political idea – using someone – the victim.6

The

subject of enforced disappearances in Guatemala had been included in the

Comprehensive Agreement on Human Rights signed on 29 March 1994

7, under Commitment III,

Commitment against Impunity, in which the State undertook to promote the

legal amendments to the Criminal Code to describe enforced disappearance

as a crime of particular gravity. The Government likewise undertook to

support recognition in the international community of the definition of

systematic enforced disappearances as a crime against humanity. The

subject of enforced disappearances in Guatemala had been included in the

Comprehensive Agreement on Human Rights signed on 29 March 1994

7, under Commitment III,

Commitment against Impunity, in which the State undertook to promote the

legal amendments to the Criminal Code to describe enforced disappearance

as a crime of particular gravity. The Government likewise undertook to

support recognition in the international community of the definition of

systematic enforced disappearances as a crime against humanity.

On 14 July 1995, Legislative Decree 48-1995 was

enacted, whereby article 201-ter was added to the Criminal Code, thereby

criminalizing the conduct of enforced disappearance. Article 201-ter of

the Guatemalan Penal Code, as amended by Decree 33-96 of the Congress of

the Republic, approved on 22 May 1996, stipulates that:

[t]he crime of forced disappearance is committed by

anyone who, by order or with authorization or support of State

authorities, in any way deprives a person or persons of their liberty,

for political reasons, concealing their whereabouts, refusing to

reveal their fate or recognize their detention, as well as any public

official or employee, whether or not they are members of the State

security forces, who orders, authorizes, supports or acquiesces in

such actions.

The Criminal Code provides for a penalty of 25 to 40

years of imprisonment and, in the event of the death or serious physical

or psychological harm of the victim of enforced disappearance, capital

punishment is envisaged.8

Ongoing Impunity

The

Inter-American Court of Human Rights rendered a number of judgments9

on cases of enforced disappearance that happened during the Guatemalan

armed conflict, where, besides declaring the international

responsibility of the State for the violation of various human rights

(right to life, right to humane treatment, right to personal liberty,

right to a fair trial and right to judicial protection), the Court

ordered the State, among other measures of reparation, to "exhaust all

the procedures necessary in order to guarantee, within a reasonable

period of time, the effective compliance of its duty to investigate,

prosecute, and, if it is the case, punish those responsible for the

facts […], as well as ensure the victims’ right to a fair trial"10.

The Court also added that "the result of the proceedings must be made

public, so that the Guatemalan society can know the truth"11. The

Inter-American Court of Human Rights rendered a number of judgments9

on cases of enforced disappearance that happened during the Guatemalan

armed conflict, where, besides declaring the international

responsibility of the State for the violation of various human rights

(right to life, right to humane treatment, right to personal liberty,

right to a fair trial and right to judicial protection), the Court

ordered the State, among other measures of reparation, to "exhaust all

the procedures necessary in order to guarantee, within a reasonable

period of time, the effective compliance of its duty to investigate,

prosecute, and, if it is the case, punish those responsible for the

facts […], as well as ensure the victims’ right to a fair trial"10.

The Court also added that "the result of the proceedings must be made

public, so that the Guatemalan society can know the truth"11.

Nevertheless,

for almost 30 years, the majority of reported cases of enforced

disappearance during the armed conflict remained unsolved.

12 Since enforced disappearance was

codified as a separate crime under domestic penal law in 1996, the

mentioned provision remained dead letter for more than 10 years. In

fact, until 2007, there was not a single person arrested or tried for

the commission of the crime of enforced disappearance. Only two cases

made their way up to the stage of formulating an accusation. The two

cases referred to enforced disappearances which had occurred between

1981 and 1984. The defendants invoked the principle of non-retroactivity

of criminal law and claimed that they could not be charged with the

crime of enforced disappearance as Article 201-ter had been introduced

in the Criminal Code only in 1996 that is many years after the events.

The issue went to the Guatemalan Constitutional Court. Nevertheless,

for almost 30 years, the majority of reported cases of enforced

disappearance during the armed conflict remained unsolved.

12 Since enforced disappearance was

codified as a separate crime under domestic penal law in 1996, the

mentioned provision remained dead letter for more than 10 years. In

fact, until 2007, there was not a single person arrested or tried for

the commission of the crime of enforced disappearance. Only two cases

made their way up to the stage of formulating an accusation. The two

cases referred to enforced disappearances which had occurred between

1981 and 1984. The defendants invoked the principle of non-retroactivity

of criminal law and claimed that they could not be charged with the

crime of enforced disappearance as Article 201-ter had been introduced

in the Criminal Code only in 1996 that is many years after the events.

The issue went to the Guatemalan Constitutional Court.

The Judgment by the Constitutional Court

In a groundbreaking judgment of 7 July 2009, the

Guatemalan Constitutional Court found that, as the crime of enforced

disappearance is a continuing (or permanent) one, it lasts until the

fate and whereabouts of the disappeared person are established with

certainty.13 Accordingly,

there is no breach whatsoever of the principle of non-retroactivity of

criminal law: as long as the perpetrators do not disclose the fate and

whereabouts of the victim, the crime continues being committed,

regardless of when the deprivation of liberty of the disappeared person

originally occurred. The Court went on to find that in such cases, there

is no retroactive application of the law even if the conduct commenced

before the relevant article of the Criminal Code entered into force,

given that it continued after that date.

The decision has, for the first time, opened the door

to prosecutions for the tens of thousands of enforced disappearances in

Guatemala and to an end to the impunity that has reigned to date.

The first Two Convictions for Enforced Disappearance

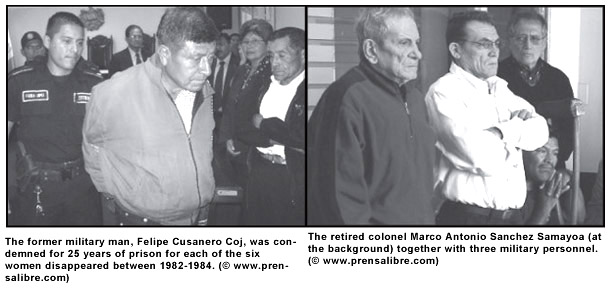

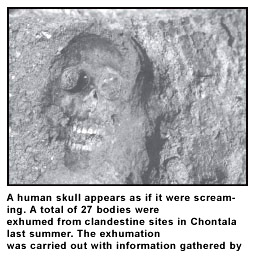

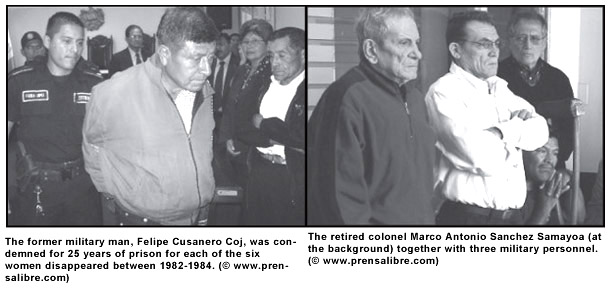

In 2003, relatives of six people14

who were victims of enforced disappearance between 1983 and 1984 in the

Choatalum village, filed a complaint against the former military

commissioner Felipe Cusanero Coj, claiming that he was responsible for

the mentioned crimes. He was charged with the crime of enforced

disappearance as defined by Article 201-ter of the Criminal Code.

On 7 September 2009 the first conviction for enforced

disappearance was eventually passed: Felipe Cusanero Coj was sentenced

to 150 years jail (25 years of prison for every disappeared person).15

The sentence implied the immediate capture of Mr. Cusanero.

The

judgment reiterated the permanent nature of the crime, which the

Constitutional Court had already cleared up. Moreover, the judges based

their decision on the evidence presented by the attorney for the

government and the plaintiff. Amongst the pieces of evidence are the

testimonies of the relatives who witnessed the arbitrary deprivation of

liberty during those years; as well as forensic reports that proved the

existence of a military detachment in the place; the Guatemala Nunca

Más (Never Again) Report, the Memoria del Silencio (Memory of

Silence) Report; and reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human

Rights.16 The

judgment reiterated the permanent nature of the crime, which the

Constitutional Court had already cleared up. Moreover, the judges based

their decision on the evidence presented by the attorney for the

government and the plaintiff. Amongst the pieces of evidence are the

testimonies of the relatives who witnessed the arbitrary deprivation of

liberty during those years; as well as forensic reports that proved the

existence of a military detachment in the place; the Guatemala Nunca

Más (Never Again) Report, the Memoria del Silencio (Memory of

Silence) Report; and reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human

Rights.16

Finally, the judgment refers to further prosecution

proceedings that the public prosecutor shall institute, as names of two

other allegedly involved military officials emerged during the trial.

On 3 December 2009, another Guatemalan tribunal

handed down a second landmark judgment, sentencing Coronel Marco Antonio

Sánchez Samayoa and the 3 military commissioners José Domingo Ríos,

Gabriel Álvarez Ramos and Salomón Maldonado Ríos to 53 years in prison

for the enforced disappearance of 8 people17

perpetrated in 1981 in the village of El Jute.18

Coronel Sánchez Samayoa, who was the Commander of the

Military Zone of Zacapa, is the first high-ranking member of the

military convicted for enforced disappearance committed during the

internal armed conflict: the prosecutors successfully proved that, given

his position and functions, he was aware of counter-insurgency

activities carried out against suspected members of the guerrilla,

including the disappearance of the 8 victims in the case.

This judgment is particularly important also because,

in order to bring the case to trial, prosecutors and representatives of

the victims successfully challenged a Court of Appeals decision of 2006,

in which Coronel Sánchez Samayoa was granted an amnesty under the 1996

National Reconciliation Law. After a long legal battle, that decision

was overturned, following a Constitutional Court ruling which recognised

that certain crimes, including enforced disappearance, are excluded from

the ambit of the law.19

The judgment also orders to the public prosecutor to

initiate an investigation against the former Ministry of the Defence

Ángel Aníbal Guevara; the former Chief of Staff for the Defense

Benedicto Lucas García; and other military personnel in service in the

military base of Zacapa in 1981. Indeed, the judgment of December 2009

concretely opens the door to other significant results in the struggle

against impunity. In fact, this historical achievement has not been

welcomed by everyone: both the lawyers who represented the relatives of

the disappeared people and the relatives themselves have been subjected

to a harsh campaign of threats and harassment and are currently under a

special regime of protection.

Conclusions

The judgments delivered after almost 30 years of

impunity by Guatemalan tribunals as well as by the Constitutional Court

provide a ray of hope for the families of the 45,000 victims of enforced

disappearance from the internal armed conflict, and set important

precedents for prosecutors and judges to rely on in future cases to be

brought before the courts, not only in Guatemala, but in all those

countries where cases of enforced disappearance have occurred.

In fact, as a result of the continuing nature of the

crime of enforced disappearance, those responsible for the crime can and

must be subjected to legal proceedings and sanctions even if the law

creating the separate crime of enforced disappearance is adopted after

the initial act causing the disappearance, or if after the enactment of

the law, the fate and whereabouts of the victim would continue to remain

unknown.

It is still a long road towards accountability for

these heinous crimes, but the Guatemalan experience shows that, even if

it may take many years, impunity can eventually be defeated by truth and

justice.

1 In its final

report, the Truth Commission for Guatemala (Commission for Historical

Clarification - CEH) concluded that in the context of the Guatemalan

armed conflict acts of genocide were committed against members of Maya-Ixil,

Maya-Achí, Maya-K’iché, Maya-Chuj and Maya- Q’anjob’al peoples. See

Final Report of the CEH, Guatemala: Memory of Silence, Guatemala,

1999, Tome III, pp. 316-318, 358, 375-376, 393, 410, 416-423.

2 United Nations Working Group on

Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance (UNWGEID), Report on the

Mission to Guatemala, doc. A/HRC/4/41 of 20 February 2007, para. 9.

In 1987 the UNWGEID had carried out another mission to the country: see

doc. E/CN.4/1988/19/Add.1 of 21 December 1987.

3 The text is available at: http://www.c-r.org/our-work/accord/guatemala/firm-lasting-peace.

php.

4 While the Commission for Historical

Clarification was carrying out its mandate, a similar initiative was

undertaken also by the Guatemalan Archbishop. For the final report of

this other Truth Commission, see Archibishop of Guatemala, Human Rights

Office, Guatemala: Never Again - Report of the Inter-diocesan Project of

Recovery of Historical Memory, Guatemala City, 1998.

5 CEH, Guatemala: Memory of

Silence, supra note 1, "Conclusions", chap. IV, para. 89.

6 Ibid., para. 2061.

7 The text is available at: http://www.c-r.org/our-work/accord/guatemal/human-rights

agreement.php.

8 On the compatibility of the

Guatemalan Criminal law on enforced disappearance with international

human rights law, see UNWGEID, Report on the Mission to Guatemala,

supra note 2, paras. 28-34 and 99.

9 Inter-American Court of Human

Rights (IACHR), Case Blake v. Guatemala, judgment of 24

January 1998; Case Bámaca Velásquez v. Guatemala, judgment

of 25 November 2000; Case Molina Theissen v. Guatemala,

judgment of 4 May 2004; and Case Tiu Tojín v. Guatemala,

judgment of 26 November 2008.

10 IACHR, Case Tiu Tojín, supra

note 9, para. 72.

11 Ibid.

12 See, inter alia, Inter-American

Commission on Human Rights, Justice and Social Inclusion: the Challenges

of Democracy in Guatemala, OEA/Ser.L/V/II.118 Doc.5 rev.1, 29 December

2003.

13 Constitutional Court of

Guatemala, judgment of 7 July 2009. See also, inter alia,

Constitutional Section of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of the

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, judgment of 10 August 2007; Supreme

Court of Justice of Peru, judgment of 20 March 2006 (Exp. 111-04, D.D.

Cayo Rivera Schreiber); Constitutional Court of Peru, judgment of 18

March 2004 (Exp. 2488-2002-HC/TC), para. 26; Supreme Court of Justice of

Mexico, judgment of 20 July 2004 (P./J.49/2004); Constitutional Court of

Peru, judgment of 9 December 2004 (Exp. 2798-04-HC/TC), para. 22; and

Constitutional Court of Colombia, judgment of 31 July 2002 (No.

C-580/02).

14 Lorenzo Ávila, Alejo Culajay Ic,

Filomena López Chajchaguin, Encarnación López López, Santiago Sutuj and

Mario Augusto Tay Cajt.

15 Tribunal for Criminal Act,

Narco-activity and Crimes against the Environment of the region of

Chimaltenango, Judgment No. C-26-2-2006, Of. III, 7 September 2009.

16 Inter-American Commission on

Human Rights, Report on the Human Rights Situation of Human Rights in

the Republic of Guatemala, doc. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.53 Doc. 21 rev. 2 of

13 October 1981 (Chapter II, Missing Persons); and doc. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.61

Doc. 47 of 3 October 1983 (Chapter III, Abductions and Disappearances).

17 Jacobo Crisóstomo Chegüen, Miguel

Ángel Chegüen Crisóstomo, Raúl Chegüen, Inocente Gallardo, Antolín

Gallardo Rivera, Valentín Gallardo Rivera, Antolín Gallardo Rivera and

Santiago Gallardo Rivera.

18 Tribunal of Chiquimula (Tribunal

Primero de Sentencia), judgment of 3 December 2009. More precisely, the

accused were sentenced to 40 years of imprisonment for enforced

disappearance and to 13 years and 4 months of imprisonment for illegal

deprivation of liberty.

19 Constitutional Court of

Guatemala, judgment of 23 December 2008. See ttp://www.

impunitywatch.org/en/publication/36.

Ph.D. Gabriella Citroni is

Researcher in International Law and Professor of International Human

Rights Law at the University of Milano-Bicocca (Italy) as well as

international legal advisor of the Latin American Federation of

Associations of Relatives of Disappeared People (FEDEFAM).

VOICE March 2010

UP

MIDDLE

DOWN

|

The

subject of enforced disappearances in Guatemala had been included in the

Comprehensive Agreement on Human Rights signed on 29 March 1994

The

subject of enforced disappearances in Guatemala had been included in the

Comprehensive Agreement on Human Rights signed on 29 March 1994

The

Inter-American Court of Human Rights rendered a number of judgments

The

Inter-American Court of Human Rights rendered a number of judgments Nevertheless,

for almost 30 years, the majority of reported cases of enforced

disappearance during the armed conflict remained unsolved.

Nevertheless,

for almost 30 years, the majority of reported cases of enforced

disappearance during the armed conflict remained unsolved.  The

judgment reiterated the permanent nature of the crime, which the

Constitutional Court had already cleared up. Moreover, the judges based

their decision on the evidence presented by the attorney for the

government and the plaintiff. Amongst the pieces of evidence are the

testimonies of the relatives who witnessed the arbitrary deprivation of

liberty during those years; as well as forensic reports that proved the

existence of a military detachment in the place; the Guatemala Nunca

Más (Never Again) Report, the Memoria del Silencio (Memory of

Silence) Report; and reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human

Rights.

The

judgment reiterated the permanent nature of the crime, which the

Constitutional Court had already cleared up. Moreover, the judges based

their decision on the evidence presented by the attorney for the

government and the plaintiff. Amongst the pieces of evidence are the

testimonies of the relatives who witnessed the arbitrary deprivation of

liberty during those years; as well as forensic reports that proved the

existence of a military detachment in the place; the Guatemala Nunca

Más (Never Again) Report, the Memoria del Silencio (Memory of

Silence) Report; and reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human

Rights.